Illegitimacy Records in England

22

22Nov

Illegitimacy was not as common in England during the 16th and 17th centuries as it later became. From 1575 to 1834, the parents of bastard children could be punished. Men could be imprisoned unless they provided security which would relieve the parish from financial maintenance of their children; women could be sent to the workhouse and/or whipped.

For many years, an illegitimate child could not claim legal residence in the parish of his father or mother because he was not legitimate. Hence, his legal place of residence was considered the parish where he was born. As single women with illegitimate children usually required parish relief, pregnant women were often moved out of a parish by its officials to prevent the mother from giving birth within the parish boundaries and thus making the child chargeable to the parish. This practice ended with the Act of 1743-4 which stated that an illegitimate child born in a parish other than where the mother was legally settled was to have its mother’s settlement.

When parish officials could not force a couple to marry, they would attempt to make the father responsible by bond for the financial maintenance of the child or would allow him to pay a lump sum in lieu of future responsibility.

An illegitimate child could be made legitimate by the subsequent marriage of its parents. Therefore, an illegitimate child christened under the mother’s maiden name might later be known by the father’s surname. If a woman married shortly after the birth of an illegitimate child, it is possible that her husband was the biological father of the child. In addition, children born more than a month after marriage were considered legitimate.

Unfortunately, birth certificates and christening records rarely provide the name of an illegitimate child’s father. A marriage certificate may indicate illegitimacy when the column requesting the father’s name is left blank. Sometimes the father would be named if the bride or groom knew him; other times the illegitimate party would manufacture a father’s name (usually by substituting the mother’s surname) in order to appear legitimate.

Christening records infer illegitimacy by using terms such as “illegitimate,” “baseborn,” “natural,” “bastard,” or “born out of wedlock.” A christening entry may occasionally include the name of the “presumed father” but most illegitimate births were recorded solely under the name of the single mother. For some illegitimate births, the name of the biological father (or at least the name of the father as claimed by the mother) may be found in other parish records or in ecclesiastical courts.

Parish Chest Records

Business and welfare records of the parish were usually stored in the same parish chest as the parish registers. Business records of the parish might pertain to highway maintenance, parish expenditures, collection and distribution of welfare assistance, and other matters managed by parish officials.

Records relating to illegitimacy may be found in Overseer of the Poor records, Churchwarden Accounts, or Vestry Minutes. Single mothers of illegitimate children and pregnant single women were interviewed by parish officials and the Justice of the Peace when it appeared that their children were likely to become chargeable to the parish. The purpose of the interview was to determine the name of the father who would then be charged with financial maintenance for the child. The interview (known as an Examination) and perhaps a Maintenance Order and a Warrant for Arrest may be found amongst the parish’s records.

In cases where the family of a single pregnant woman agreed to take full financial responsibility for the unborn child, the parish was relieved of the burden and records stating the name of the biological father were not likely created. Records may also not have been kept when the biological father agreed to make voluntary payments directly to the mother and not to the parish.

Many parish chest materials are found today at county record offices or local churches. A county record office’s online catalog could be searched for parish chest records by using the parish name and the type of record sought (e.g., bastardy bonds). A growing collection of parish chest materials have been microfilmed and are found at the Family History Library. To locate these records on film, the FamilySearch catalog would be searched for the parish of interest, and then for “Church Records” or “Poorhouses and Poor Law.” Existing records may include the following:

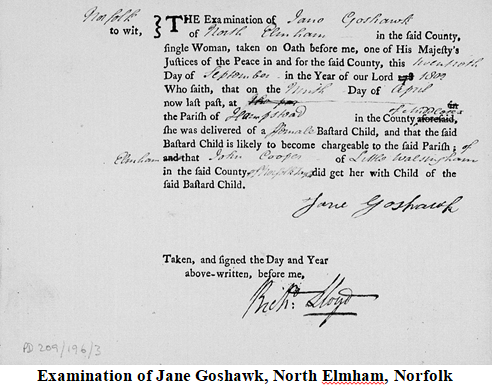

Examination

Parish officials and the Justice of the Peace interrogated unmarried pregnant women to identify the father so that financial responsibility for the child would be placed upon the father and not the parish. The examination included some details about the mother, the child, and the father (including the father’s name, occupation and residence).

Warrant for Arrest, Maintenance Order

If the man named by an unmarried pregnant woman had left the parish, a Warrant for Arrest might be issued by a Justice of the Peace to apprehend the man and bring him back for questioning. When brought to the court, the man would be questioned as to why he should not be adjudged the biological father. If the Justice of the Peace found reason to conclude that he was indeed the father, then a Maintenance Order would be issued and the father was obligated to provide financial care for his illegitimate child. The Maintenance Order detailed the financial obligation (amount to be paid and the frequency of payments) and provided basic information concerning both parents. (Tip: When parish chest records do not contain information about an illegitimate birth, search the records of the Court of Quarter Session from the time the woman became pregnant through the first year after birth. As the Warrant for Arrest and the Maintenance Order were issued by the Justice of the Peace, copies may be found in these court records.)

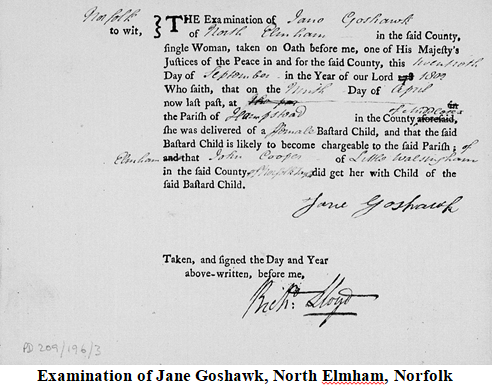

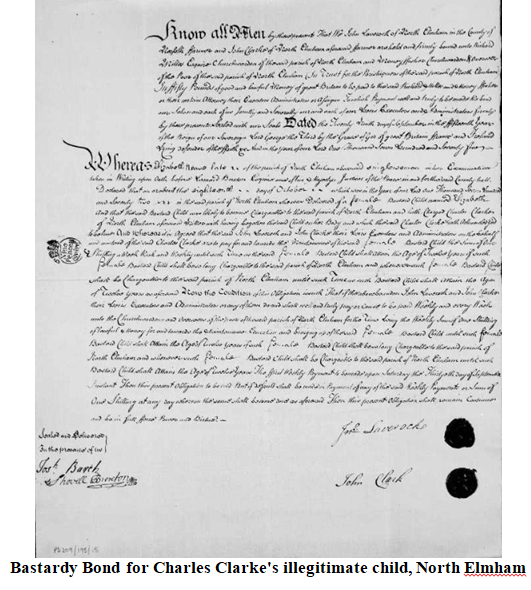

Bastardy Bond (Bond of Indemnification)

The bond was a father’s guarantee to provide financial support for his illegitimate child. The father could make regular payments to provide for his child or pay one lump sum.

Vestry Minutes, Churchwarden Accounts

A bond of indemnification might be bypassed by a “gentlemen’s agreement” and information may then be found in the Vestry Minutes or in the Churchwarden Accounts. Voluntary payments by the father to parish officials were often noted in their records. Sometimes a lump sum was agreed upon by the father (or his relatives) and the parish which would cover the child’s maintenance until the child reached adulthood. Such an agreement may also have been recorded in the Vestry Minutes.

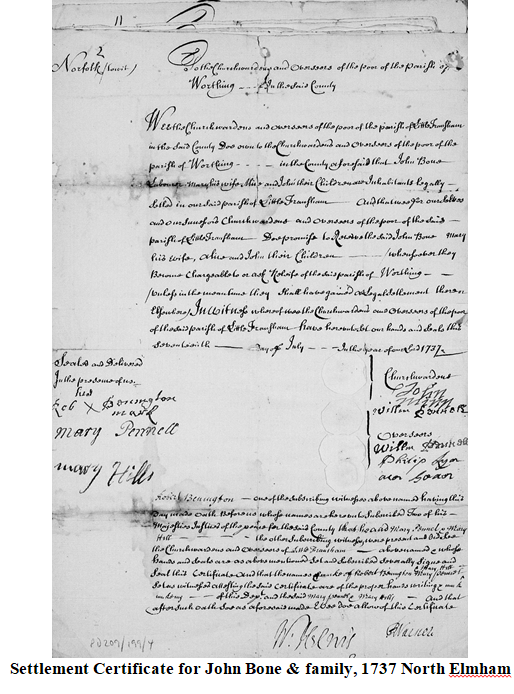

Removal Orders, Settlement Certificates, Settlement Examinations

Parish records regarding one’s legal place of settlement occasionally include references to illegitimacy. These documents may be found in Overseer of the Poor records or Churchwarden Accounts.

Ecclesiastical Court Records

Church of England courts may hold records of interest for illegitimacy cases. Couples who married in ways not recognized as being legal may have been brought to a church court and charged with fornication. This is particularly true for Catholics who were married by their parish priest. Children born into an illegal union were considered bastards. Church court records may be found at county record offices.

Prior to 1858, probate was handled by ecclesiastical courts of the Church of England. Testators sometimes mentioned their “natural” children in their wills. Most wills prior to 1900 have been microfilmed and are available at the Family History Library. Many wills are being digitized and are increasingly available at FamilySearch or commercial websites such as Ancestry and FindMyPast. A few are still only available for purchase by the archive that holds the original record.

At Price Genealogy we have over forty years of experience helping people with their English genealogy and with the Poor Law records and illegitimacy. We are happy to help you break through your brick walls as well.

Apryl