Tax Records

21

21Apr

Nobody likes taxes, and that wasn’t any different for our ancestors. Just like us, our ancestors had to pay their taxes, and records of them were kept. These tax records are of value to genealogists today.

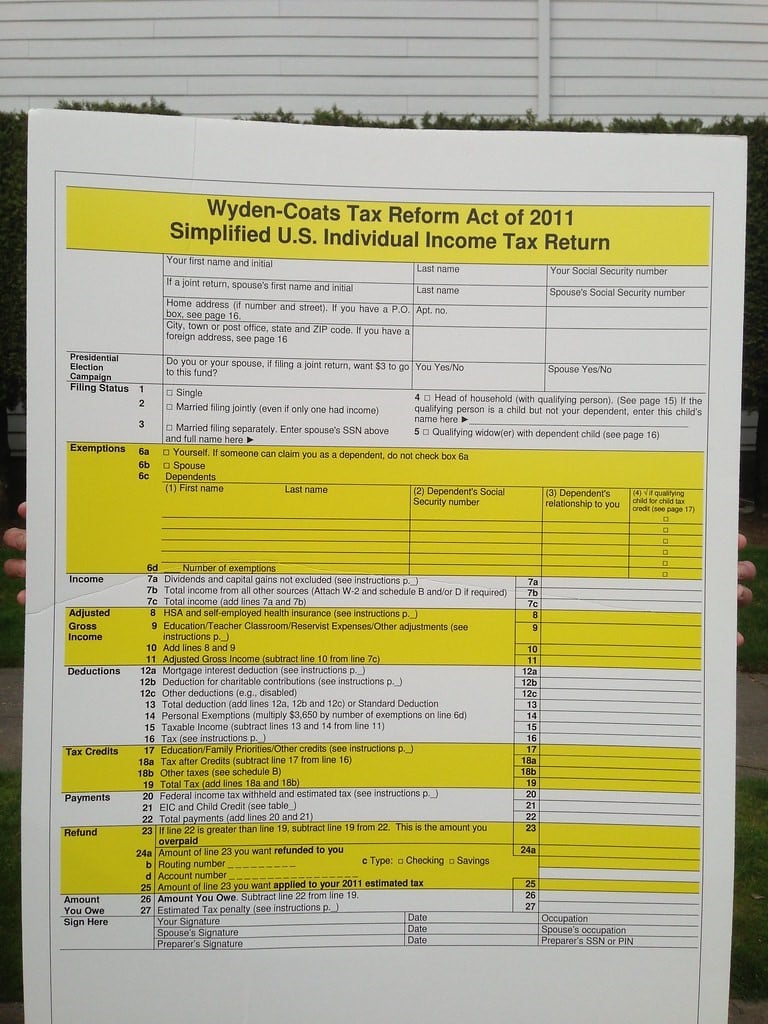

Just like your tax return includes federal, state, and local taxes, your ancestor was also taxed at various jurisdiction levels. Therefore, you should look at every jurisdiction level for tax records of your ancestor: city, county, state, and federal.

[i] Governments use the tax money to fund their programs. Modern taxes fund schools, libraries, road construction, government aid programs, wars, etc. This was very similar a century or more ago. Specific programs funded by the government have changed over the years, and so have the tax laws. But the concept of tax money to fund government programs has remained the same. A poll tax may have been placed where your ancestor lived to fund the building of a school or a courthouse.

Governments use the tax money to fund their programs. Modern taxes fund schools, libraries, road construction, government aid programs, wars, etc. This was very similar a century or more ago. Specific programs funded by the government have changed over the years, and so have the tax laws. But the concept of tax money to fund government programs has remained the same. A poll tax may have been placed where your ancestor lived to fund the building of a school or a courthouse.

In the early days of our country, states often imposed a poll tax, which was a fixed tax on free, white, males within a certain age range. The head of household had to pay this for every qualifying person in his household. In some cases, a poll tax was charged for slaves and servants. Pennsylvania only charged the poll tax to single males to encourage marriage. Poll tax records would name the head of household and state how many other taxable people who were in the household.

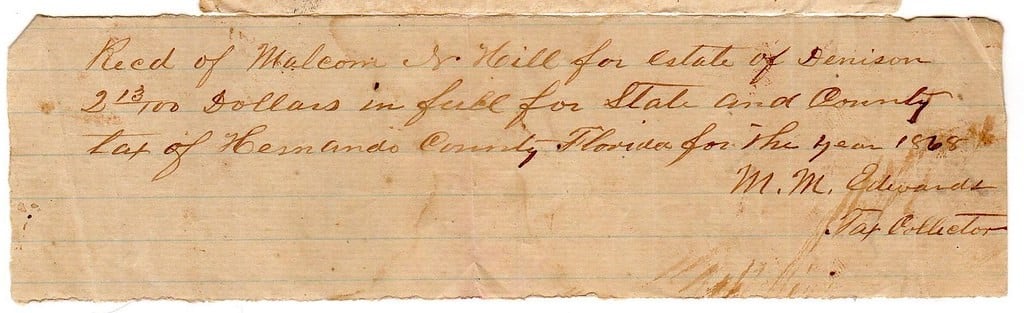

Property tax was paid by property owners based on what property they owned. Both real estate and personal estate were taxed. The tax records for this kind of tax included what property was being taxed, including acreage and quality of land for real estate. Property tax also included estates of deceased men whose property had not yet gone to his heirs. Where personal property was taxed, the items owned by the taxpayer were recorded.

Some states recorded the poll and property taxes on the same record. With poll tax records, you can determine when a household had a son who came of age to be taxable and when that same son become old enough to pay his own taxes. This makes it possible to estimate his birth year. With property tax records, you can see what your ancestor owned and get clues to look for land records of your ancestor. A change in quantity of land owned by your ancestor would suggest a sale or acquisition of land.

Because no one’s excited about taxes, some people tried to evade them. A young man who just became of taxable age may not have started paying taxes right away. People paying taxes on personal estate may have underreported what they owned. Some counties and states kept lists of delinquent taxpayers. If an ancestor couldn’t pay his property taxes, a lien was placed on his property until he could pay it, and this would have left a paper trail. Sometimes the government would use tax exemptions to encourage migration or to promote certain industries. Homesteaders were exempt from paying taxes on their homestead land.

Tax records available for your ancestors depend on when and where they lived. Go to the FamilySearch Wiki page for your ancestor’s county or state and click Tax Records. You will be taken to a list of available resources to search for tax records for that area; choose the resources applicable to your ancestor’s time. FamilySearch and Ancestry both have some tax records digitized. Ancestry’s searchable tax record databases can be found here. To find tax records on FamilySearch, go to the Card Catalog and do a search for tax records and your ancestor’s area. This will pull up digitized collections, some indexed and some not; and it will pull up microfilm and book collections available at the FamilySearch Library. The non-indexed records are sorted by location and year, so you can find your ancestor via browsing if you know specifically where they lived.

Tax records were utilized in research for candidates for the father of James Axley Griffitts’ father. Census records had identified a John Griffith in Tazewell County, Virginia and another in Morgan County, Tennessee. Men of this surname and its spelling variations (Griffitts, Griffit, Griffets, Griffy, Griffey, Griffith, Griffeth) were searched for in Tazewell County, Virginia tax records from 1801 to 1850.[ii]

When there are multiple men with the same name in the same area, the tax collector makes a notation to differentiate them. Of the Georges listed from the 1830s to the 1850s, they were designated as George of Jno and George of Wm. George written without a suffix or notation was noted separately by the researcher. The tax collectors weren’t always consistent with how they differentiated people with the same name, so the George with no annotation could be either of the other two for any year he was listed. In 1842 and 1843, he can’t be George of Jno because he had his own entries on the tax lists that year.

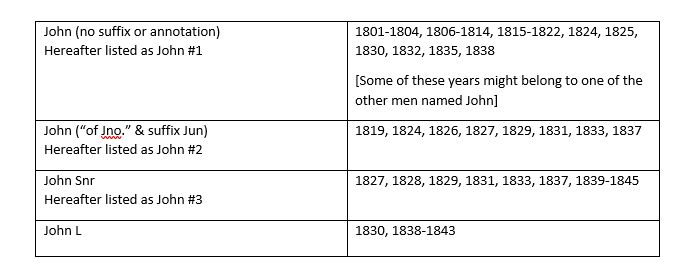

There were a lot more Johns listed than Georges. The John with no suffix or annotation was designated as John #1, John of Jno/John Jun was designated as John #2, and John Snr was designated as John #3. Listed in 1819 was the estate of John Griffey, who presumably died shortly before. A John L. was also listed. John #1 could be any of the other Johns if the tax collector left out the Snr or Jun or left out the middle initial of John L.

By combining the above tax list evidence with other evidence, the researcher was able to make the following observations:

- The fact that John #1 firsts appears there in 1801 makes him old enough to be the father of John Griffith from the 1850 and 1860 Morgan County, Kentucky censuses.

- The starting date that John #2 first shows up on the tax lists suggests he is close enough in age to be the John from the 1850 and 1860 Morgan County, Kentucky censuses. John #2 and John L. might be the same person. They do not have any conflicting dates.

- The date when John #3 drops off the Tazewell County, Virginia tax list is the year before John Griffitts first appeared on the Morgan County, Kentucky tax lists.

Just like with the Griffitts/Griffth research, consecutive tax lists in an area can be compared to establish residency of ancestors and potential relatives. Appearances on tax lists either indicate the man came of taxable age or migrated to the area. Disappearances from tax lists either indicate the man moved away or died. A disappearance on one tax list coinciding with an appearance on another tax list, as in the case of John #3, suggests a migration. As with the case with the Johns and the Georges above, tax lists can point out when there were multiple men with the same name in a community and help you tell them apart.

Because tax records identified John L. Griffith, John Griffeth #2, and John Griffeth #3 as possible candidates for James Axley Griffitts’ father, further research will be done on those men. The 1819 tax listing of John Griffith’s estate is a strong hint to search probate records for him.

Tax records can help in your research by establishing residence, giving dates to estimate birth and death from, and giving clues to land ownership. If you need help researching your ancestors in tax records, Price Genealogy can help.

By Katie

[i] All photos are public domain

[ii] Tazewell County, Virginia Commissioner of the Revenue, Personal property tax lists of Tazewell County, Virginia 1801-1850 (Salt Lake City, Utah: Filmed by the Genealogical Society of Utah, 1955) viewed through FamilySearch catalog page 12/5/2022 at https://bit.ly/3F35YKa.