Tracing LGBT Ancestors

30

30Jun

All family trees include a variety of people – some who led remarkable lives and others who lived more quietly; from rogues to royalty; those with large families and those without children; individuals who married multiple times and others who never married at all. Likewise, queer individuals have always been part of history, and it is highly likely that most family trees include LGBT ancestors, even if their stories have not always been fully told.

Genealogists and historians increasingly recognize that same-sex relationships have existed throughout recorded history, even if these relationships were not always described or acknowledged in the ways understood today. Modern historical records offer numerous documented cases—sometimes explicit, often coded—of enduring romantic or sexual relationships between people of the same sex.

These relationships rarely conformed to public norms and could carry severe social consequences. Homosexual acts were criminalized in many European and American jurisdictions, often punishable by death or public humiliation. Yet, the persistence of these relationships—sometimes hidden, sometimes defiant—demonstrates the resilience of queer individuals throughout history. For genealogists, uncovering these stories requires reading archival documents with sensitivity to coded language, context, and the silence that often surrounds forbidden love. In doing so, we help restore the voices of those whose lives and loves were once erased from the historical narrative.

What Records to Use

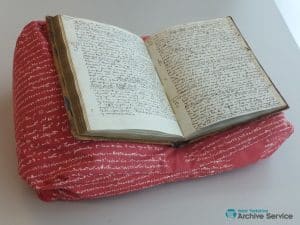

Start by looking for personal accounts, such as letters and diaries. One of the most frequently cited examples is that of 18th-century English women Anne Lister (1791-1840) and Ann Walker (1803-1854). Lister, often called “the first modern lesbian,” kept extensive diaries—partially written in code—detailing her sexual and emotional relationships with women. In 1834, she and Walker took communion together in what they considered a form of marriage. Lister's diaries, now held at the West Yorkshire Archive Service, offer invaluable insight into the private lives of same-sex couples in a time when homosexuality was criminalized for men and socially invisible for women.

But such an obvious conclusion about sexual orientation is not always present. Women of the 18th and 19th century were known to have written passionate letters to female friends. Expressions of love and admiration toward the same gender were much more common then than they are today. In some cases, especially among women, long-term companions might be described as "Boston marriages"—close, sometimes romantic partnerships that enabled women to live independently of men.

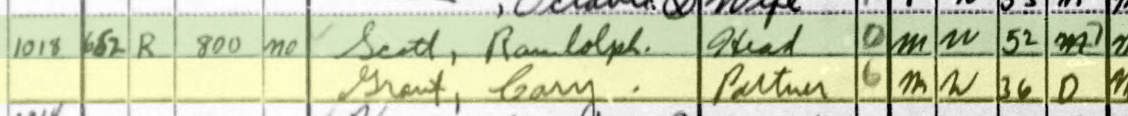

Census records are the bread and butter of most genealogical research. They are used to trace long-term relationships such as traditional families. But those living in non-traditional relationships were often guarded about claiming such relationships. Words you may encounter include “partner,” “friend,” or “joint friends and owners.” The famous actor Cary Grant was enumerated in 1940 with longtime friend Randolph Scott in Santa Monica, California, as his “Partner.”

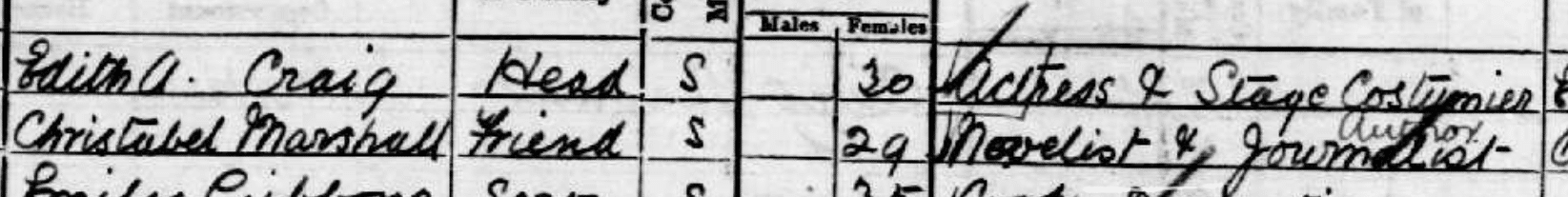

In 1901 England, Christabel (or later Christopher) Marshall (age 29) was the “Friend” of Edith A Craig (age 30). Edith was an Actress and Stage Costumier and Christabel was a Novelist and Journalist/Author. She wrote about her relationship with Craig in her journal, The Golden Book (1911). The couple lived together until 1939.

Be careful making assumptions, however, as platonic friendships were also common and can be found in the census records. Look for patterns of longevity, as well as additional evidence of a romantic attachment.

You may also find accounts in court records. For most of history, gay men were criminalized for homosexuality, much more frequently than women. Earlier examples include legal records from Renaissance Italy, such as those compiled by historian Guido Ruggiero. His research into Venetian court cases reveals numerous incidents of male same-sex relationships prosecuted as sodomy—charges that paradoxically help preserve evidence of these relationships. For example, in 16th-century Venice, men were sometimes caught and tried for repeated consensual relationships, suggesting a level of emotional attachment that extended beyond casual encounters.

Similarly, in colonial New England, court records occasionally documented accusations of "sodomy" or "lewd behavior" between men, sometimes accompanied by testimony indicating long-term domestic arrangements. In England, sodomy was punishable by death. England’s National Archive Discovery Catalogue has dozens of court cases for lewd behaviour, sodomy, and gross indecency including one for Thomas Whittaker who was convicted at the Assizes at York on 10 December 1850. He was only 18 years old, a woolsorter. He was sentenced to death, which was later commuted to life. He received an early release from Portsmouth prison on 31 December 1861. A Kent Quarter Sessions “Certificate from Marden against Thomas Burden and John Pattenden for their lewd behaviour,” leaves the reader uncertain of the relationship between them.

In more recent times, you may find a reference to an ancestral relation in historical newspapers detailing arrests, court cases, libel or defamation charges. The public court case of Sir Oscar Wilde and his partner Lord Alfred Douglas for “gross indencency” resulted in Wilde’s imprisonment for two years from 1895 to 1897.

A person’s distribution of assets after death often reveals their closest relationships, such as spouses and children; however, other relationships are also often mentioned. Wills may include phrases such as “to my beloved friend” or “faithful companion.” Bequests of land, wealth, or personal items to non-relatives of the same sex can suggest deep emotional or domestic ties. As with most other sources, the references are veiled in ambiguity, so be careful about making assumptions without other pieces of evidence.

Gravestone inscriptions also hint at deep emotional partnerships between same-sex individuals. Share burial plots, joint epitaphs, or commemorative inscriptions can suggest significant same-sex bonds. Fulke Greville, 1st Baron Brooke (1554–1628), served as Chancellor of the Exchequer under King James I and was a lifelong companion of the Elizabethan poet Sir Philip Sidney, with whom he had shared a close friendship since childhood. Greville never married, and throughout his life he formed deep and lasting friendships with other men. Greville was buried in the Church of St Mary in Warwick, where his tomb bears an epitaph that honors his public service and his bond with Sidney:

Servant to Queene Elizabeth

Counsellor to King James

And Friend to Sir Philip Sidney

The joint tomb of Sir John Finch (1626-82) and Sir Thomas Baines (1622-80) rests in the chapel of Christ’s College, Cambridge. It memorializes, in Finch’s words, the beautiful and unbroken marriage of souls, a companionship undivided during 36 complete years.’ While such terms are ambiguous, genealogists are trained to read between the lines, examining patterns of cohabitation, inheritance, and joint burial that may reflect same-sex unions.

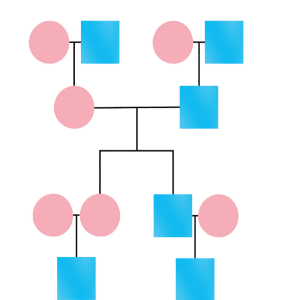

Family Tree Software

All major online family tree programs now offer same-sex capabilities, including FamilySearch.org. When this new function was released at RootsTech in 2019, Public Affairs manager Paula Nauta said “We’re adding functions that allow people to document family relationships as they exist. The goal of FamilySearch is to enable individuals to discover themselves and their families. We do that by continuing to add new services and functions that enable individuals and families to create ongoing connections and discoveries in a very fun way.” If you keep your tree online at Ancestry, you can learn how to add a same-sex relationship by visiting THIS PAGE.

While it can be argued that a same-sex couple does not represent a biological connection, it is important to note that many of us trace genealogies that are not our biological lines. For example, my grandmother was adopted. We have no biological connection to her parents, but we have a deep personal connection to them and they are very important to us. They are family, so they are part of our tree.

Conclusion

LGBT people are and always have been part of society. As one author put it, “You might not find that definitive record or letter where they define who they are. We all can’t have an Anne Lister in our family tree, writing thousands of pages of diaries.” Sometimes a lack of records for a person in a family that kept meticulous records is a clue that something is amiss/different. Ask questions. Investigate the social and historical history of the areas where your ancestors lived. Look for long-time friends, associates, and nicknames/name-changes.

Adding our LGBT ancestors to our family tree helps us to further uncover the true lives of our ancestors and share their stories alongside their traditional relatives.

If you want help uncovering the lives of your ancestors, our expert researchers at Price Genealogy can help! Contact us today.

Emily

Sources:

Photo: Brigham Morris Young (son of Brigham Young), aka Madam Pattirini, by Charles Roscoe Savage (By Charles Roscoe Savage - Photographic placard advertising "her" appearance in the Sugar House Ward, Salt Lake City, Utah (https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=27945949), Public Domain.

Photo: Explore Your Archives: Explore Archives with the Archives and Records Association, “Decoding & Transcribing Anne Lister’s diaries,” by Anna Hopkins, 3 Jun 2002 (https://www.exploreyourarchive.org/transcribing-anne-lister-diaries/)

Photo: Historic England, Graves and Monuments (https://historicengland.org.uk/research/inclusive-heritage/lgbtq-heritage-project/love-and-intimacy/graves-and-monuments/).

Whitehead, Helena, ed. I Know my own heart: the diaries of Anne Lister, 1791-1840 (New York: New York University Press, 1992). Available on Internet Archive

Ruggiero, Guideo, The Boundaries of Eros: Sex Crime and Sexuality in Renaissance Venice (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985). Available on Internet Archive.

Godbeer, Richard. The Cry of Sodom: The Problem of Male Sexuality in Puritan New England. Early American Studies, Vol. 3, No. 2, 2005.

Norton, Rictor. Mother Clap's Molly House: The Gay Subculture in England 1700–1830. London: GMP Publishers, 1992.

Faderman, Lillian. Surpassing the Love of Men: Romantic Friendship and Love Between Women from the Renaissance to the Present. New York: William Morrow, 1981.

1940 US Census, Santa Monica, Los Angeles, California, Cary Grant household; index with images, image 40 of 47, Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/2442/records/71734860?tid=&pid=&queryId=deccb38c-d175-4acc-9f47-cd1b14e21a45&_phsrc=Ccc2515&_phstart=successSource)

1901 England Census, St Margaret and St John, St George Hanover Square, London & Middlsex, Edith A Craig household; index with images, FindMyPast (https://www.findmypast.com/transcript?id=GBC%2F1901%2F0004284454&tab=this)

Deseret News, “FamilySearch completes project to allow same-sex family trees,” published 10 Dec 2019 (https://www.deseret.com/utah/2019/12/10/21004733/familysearch-same-sex-family-trees-lgbtq-geneology/)

FindMyPast, “How to trace LGBT ancestors,” by Mary Mckee, 3 Jun 2022 (https://www.findmypast.com/blog/help/lgbt-ancestors)