Bridging the Gap with Immigration and Naturalization Records

6

6Sep

Background

The United States as a nation has existed for only 243 years. In addition to the indigenous people within its boundaries, it has been continuously inhabited by Europeans and their descendants since 1565 (St. Augustine, Florida), 1598 (New Mexico, except for the 1680s) and 1607 (Jamestown, Virginia). Since the founding of the republic, every resident of the United States has either been descended from native peoples or from settlers, or came themselves from another country. American immigration and naturalization records are essential to locating where a family originated. Family historians are usually eager to find out the circumstances for how their ancestors arrived in this country.

Types of Immigration and Emigration Records

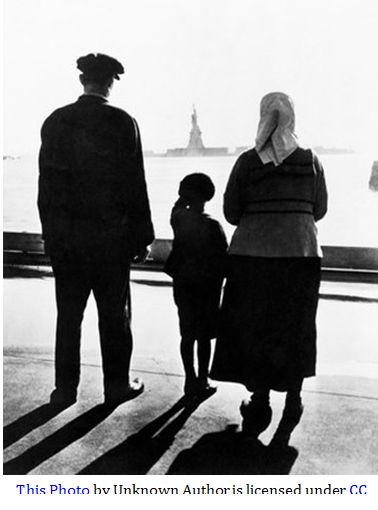

Immigration records are the documentation generated when a person enters a country. Emigration records refer to the documents created when they leave a country. One example of this is the “passenger manifest” of the ship on which they sailed. This list was typically transferred to officials in the port where the vessel landed. Beginning in the early 1800s, Boston, Philadelphia, New Orleans, Charleston, and New York City were the seaports where the majority of immigrants entered the United States. Many of the original documents have been uploaded online and are indexed for the public to view. The records for those who entered through Ellis Island (1892-1954) have been incorporated into a wonderful website—The Statue of Liberty – Ellis Island.

A second type of immigration record is the “departure passenger list” from the place of embarkation. The major emigration ports in Europe of the 19th and the 20th century were Bremen, La Havre, and Hamburg. Hamburg’s records survive, but, unfortunately, the Bremen departure lists were destroyed in a fire. The breadth of information in these two records sources spans both sides of the Atlantic. They include (but were not limited to) the name, age, and hometown of each passenger, the name and place of residence of the person they were visiting in the United States, the reason the person was traveling, and their nationality. In addition, the document(s) listed the traveler’s profession, whether he/she was employed, and their net worth. A lot of information can be gleaned from these documents, and new names can be added to pedigrees.

Naturalization Records

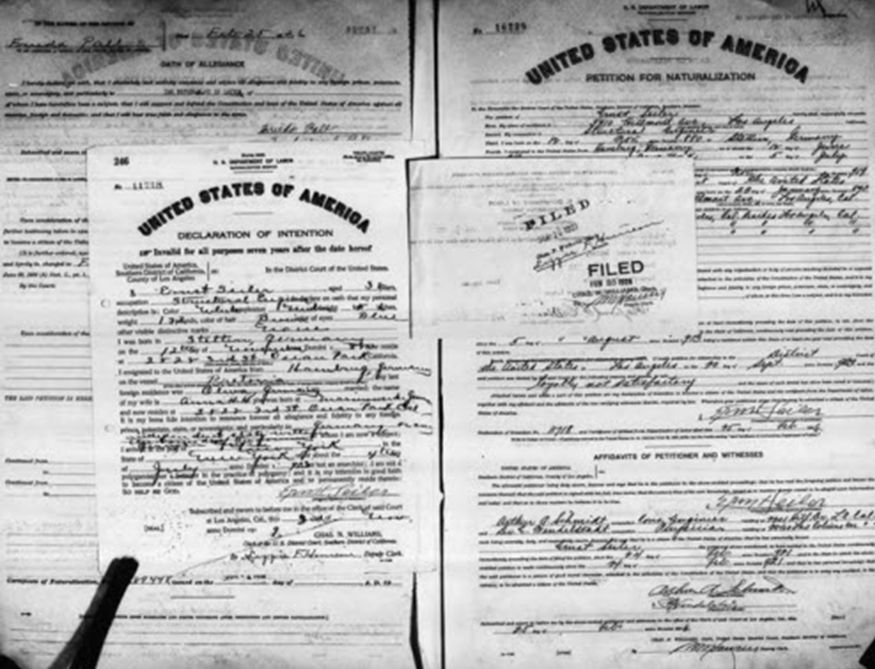

During the peak period of immigration (1880-1920), the majority of the immigrants wanted to become citizen of the United States. The process for this was called “naturalization.” It was a three-step process for a man to become a “naturalized” citizen of the United States. The first step was to apply for citizenship.[1] This was typically completed at a county court after residing in the United States for two years or more. On the application, called the “Declaration of Intent,” the applicant had to denounce his former allegiance (often to a European monarch). He provided his name, address and place of origin. He also had to list the date his ship embarked, the name of the ship, and the port and date of his arrival in the United States. A few counties chose to record the specific town of origin for the naturalized person, but this was uncommon until the system was standardized under Federal control in 1906. Beginning in this year, it was common to include the town of birth, date of birth, and other especially useful data that we generally left off earlier records.

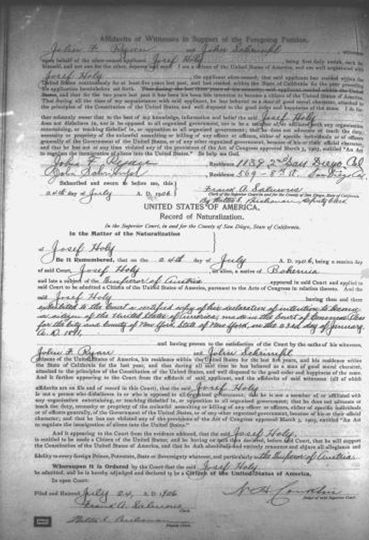

The next step in the naturalization process came after the required waiting period. The person seeking naturalization could “petition for naturalization.” This application contained much of the same information as the Declaration of Intention, and it also referred to the court where he filed his original declaration. In addition, his employment information was listed, as was his military service, if applicable. The petition included names of those who acted as witnesses and who declared affidavits supporting the applicant’s claims. If the petition was accepted, the petitioner was granted citizenship, and was given a certificate of naturalization. For immigrants who came in the mid- to late-twentieth century, there is often an entire file that can contain as much as fifty pages. The United States Citizenship and Immigration Service’s Genealogy Program provides available files of deceased immigrants for a fee upon request.[2]

The Information Found

The important thing to remember with immigration, emigration and naturalization is not the semantics, but the information that is included. The researcher should also consider the “how” and “why” of each document. The images below are examples of a Declaration of Intention and a Petition for Naturalization.[3] You can see the level of detail requested on these forms. The applicant’s name, his or her alias, date of birth and birth country, age, date of arrival, and spouse’s name are all included on the forms. There were the statements and signatures of witnesses validating the information, which can be seen at the bottom. Lastly, there was the applicant’s Record of Naturalization, signed and notarized by a judge.

Naturalization records can help reconstruct the social patterns and chain migration of our immigrant ancestors. They open the door to our family’s history on the other side of the Atlantic. Here at Price Genealogy we are experts with these records, and if your ancestors were native to the Americas, we can help with those people too!

Paul and Michael

[1]The National Archives, National Archives (https://www.archives.gov : accessed 15 August 2019), naturalization records.

[2] https://www.uscis.gov/genealogy

[3] Rootsweb.com (https://wiki.rootsweb.com/ : accessed 14 August 2019); World Archives Project: California, U.S. Naturalization Records- Original Documents, 1795-1972.