Death Records

28

28Oct

A good genealogist will use various record types in researching their ancestors, and this includes records created around a person’s death. What could be spookier than death records this Halloween?

Death records in research

Death records are the only record type with the potential to contain information about a person’s entire life span. No matter when an ancestor lived, the records created around their death are the most recent records in existence for them. If you’re researching someone’s life backwards, you might start with death records and use the clues to find other records about the person’s life. Alternatively, you may have records of a person’s life, but not know when they died, so you would need to search for death records to discover when and where they died.

In the latter situation, you might use indirect evidence of a person's death to look for death records. This can come in the form of an ancestor disappearing from records such as censuses, tax records, or directories. In some cases, the surviving spouse might appear as a widow or widower. James and Annie Davidson appeared together in the 1880 census with three children.[1] In the 1900 census, Annie was a widow who had given birth to eight children and three were living.[2] Between 1880 and 1900, James Davidson had died. Since there were large age gaps between the children in 1880 census, it can be assumed that some of her children died before 1880. Other children may have been born after 1880 and died before 1900.

Not every disappearance from records is as easy as the Davidson’s case. If both spouses die in the same decade, they will both be missing from the next census. Additionally, if the husband dies first and the wife remarries, she will appear in the census under a new married name if it’s after 1850. Before 1850, she’ll be a tick mark under her new husband. Additionally, death isn’t the only possible explanation for disappearances from records. A move would cause a man to disappear from tax lists and city directories in one area and appear in another area. A name change occurring could cause an apparent disappearance from records. In these cases, it is helpful to consider the age of the ancestor at the time in question; the older he or she would be, the more likely they are to have died. If death is suspected to be the reason for disappearance from records, then it’s time to start searching death records appropriate to the time.

Record types

The type of death record to search depends on when the person died. For people who died between 1935 and 2014, you can search for them in the Social Security Death Index (SSDI) on either FamilySearch or Ancestry. This database contains deaths of individuals who had social security numbers and whose deaths were reported to the Social Security Administration. A search in either database will pull up the name, birth date and death date.

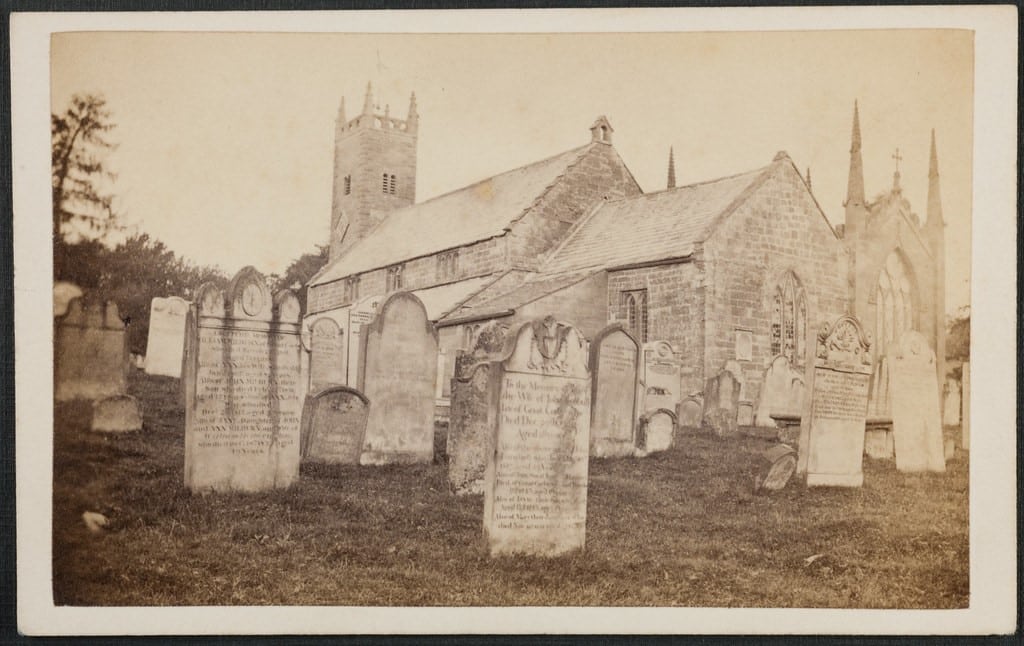

Another recent death record is death certificates. Most U.S. states began requiring statewide birth and death registration in the early twentieth century, and some states took a few decades to comply. Exact dates varies by state; you can look up the dates of vital record registration in the FamilySearch Wiki. Death certificates usually include the name of the deceased, the birth and death dates, the place of death, the cause of death, the names of the parents, the name of the informant, and where the deceased was buried. They sometimes state the places of birth for the deceased and the parents, how long the deceased was a resident of the area, the marital status, and the name of the surviving spouse. The death certificate can be a way to learn the maiden names of female ancestors. The names and birthplaces of the parents are often key information needed to extend a line back. The burial information can be used in finding additional records created around the person’s burial.

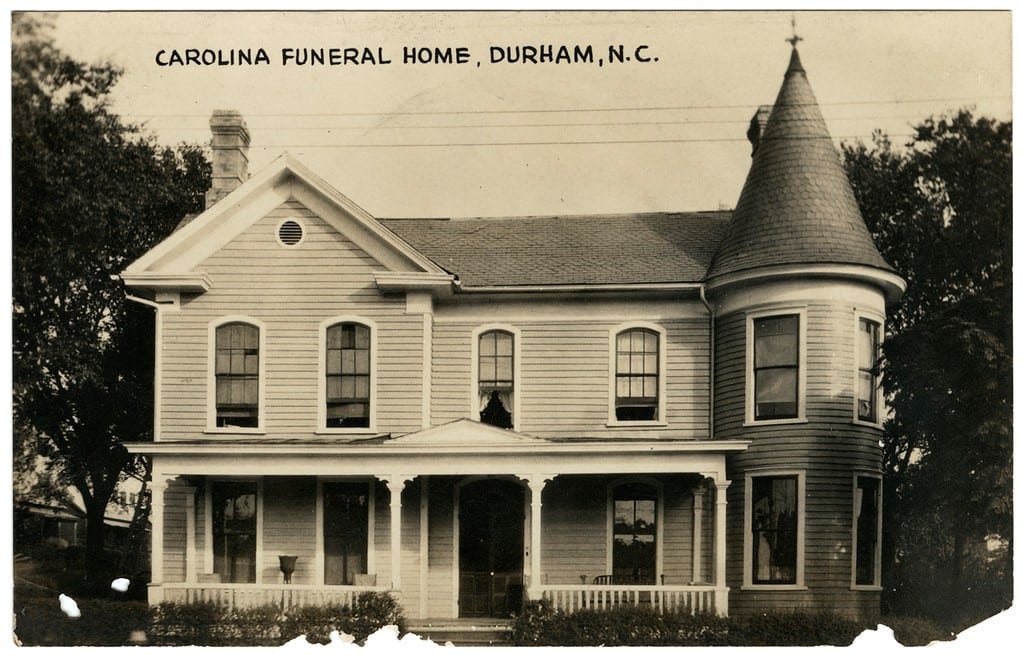

A good starting place for burial research is Findagrave or BillionGraves. Both are searchable online databases of gravestone images. The indexes of the images show the person’s name, any birth or death information from the gravestone, and the place of burial. With these kinds of databases, it is important to trust the information on the gravestone image more than on the index associated with the image, as indexes are sometimes erroneous. Even the cemetery could be erroneous due to being next to another cemetery unbeknownst to the volunteer who entered the information. However, the burial information can still be useful. Both websites have profile pages for the cemeteries which contain the contact information. By searching on Findagrave within the cemetery where Annie Davidson was buried, her deceased children were found.

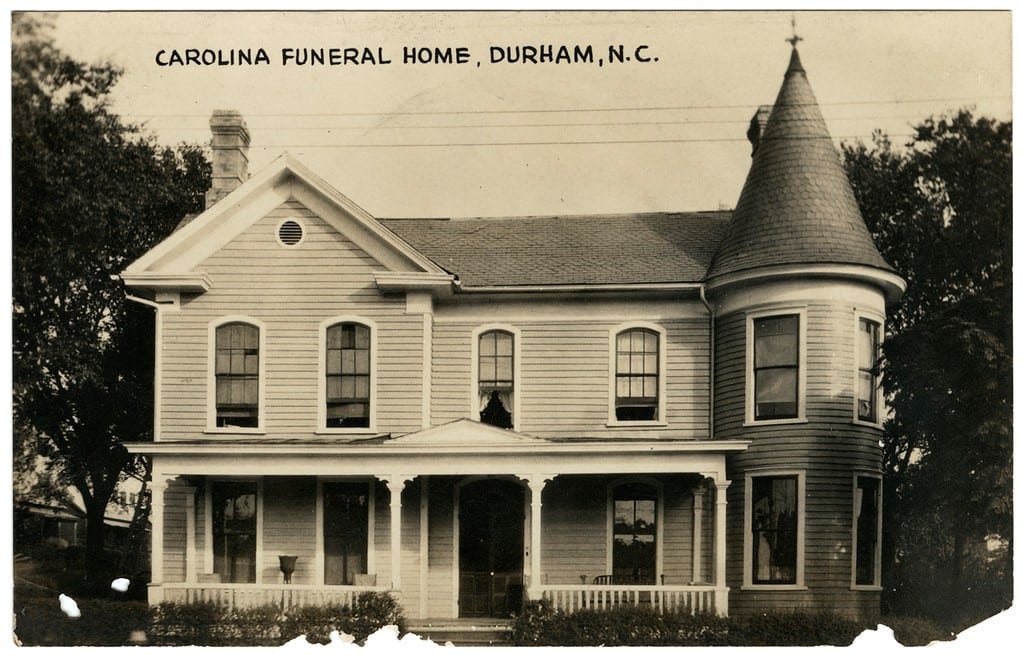

Additional records can be found by contacting the cemetery or funeral home that handled the burial if they are still in business. For old cemeteries, the records, including transcriptions of cemeteries, may be housed by local historical or genealogical societies. Sometimes the societies have their records online and other times its necessary to contact the society about obtaining the records.

Another record created around a person’s death is an obituary or death notice. Modern obituaries are published on social media. Older obituaries were published in newspapers from the nineteenth century onward. An obituary announces the death and the funeral. Sometimes they state genealogically valuable information about the deceased such as where they were born, who their family members were, what church they attended, how they died, and other information. The information contained in obituaries varies widely. The obituary of Henry Holmes, an immigrant, did not state his town of Origin, nor did it name his surviving relatives[3]. The names of surviving relatives were known from census records. It stated that his family had gone to Colorado and his destitute wife and children returned to Missouri with his dead body. Knowing that he died in Colorado and was buried in Missouri was helpful in determining where to look for additional records of him.

Before death certificates were common, some counties, towns, and churches kept death or burial registers. These registers list the names of the deceased and when they died. Some include ages or birth information. Some give names of parents or surviving spouses. Some state where the death took place, though that can often be assumed based on the locality that kept the record.

Another old death record type is probate records, including wills and guardianship records. These far predate death certificates and death registers in some areas. Before 1850, this may be the best way to determine who’s related to whom. After a person died, relatives or neighbors would go to court to begin the probate process. If the person left a will, that would state who the deceased wanted to inherit what, and it would appoint someone as an executor. If there was no will, the person died intestate, and the court would appoint an administrator. In either case, there was a process of distributing the estate to surviving relatives, or of selling belongings and giving the money to the family. If the deceased left minor children, guardians would be appointed to care for the minor children, creating additional records of interest.

Probate records listed family members who were living at the time the probate process occurred. If a relative died between the writing of the will and the proving of the will, there may have been mention of it. Other people listed on probate records include witnesses, and sometimes neighbors. These people knew the ancestral family and sometimes tracing them can help in research. Married daughters were mentioned by their married names, which can help in connecting families and confirming maiden names. If a portion of the inheritance went to a grandchild rather than a child, it suggests that the child who would have received that inheritance had died prior to the testator.

This Halloween, honor your ancestors by searching for their death records. Use the clues in their death records as you continue your research of their families. If you need help with this process, Price Genealogy can help.

By Katie

All images are public domain

[1] 1880 U.S. census, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, population schedule, Lancaster City, p. 10, dwelling 148, family 166, household of James Davidson; digital image, FamilySearch, (https://familysearch.org : accessed 28 September 2022), citing NARA publication T9.

[2] 1900 U.S. census, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, population schedule, Warwick township, p. 17, dwelling 224, family 227, household of Annie M Davidson; digital image, Ancestry, (https://ancestry.com : accessed 28 September 2022), citing NARA publication T623, roll 1424.

[3] “A short time since,” Gallatin (Missouri) Democrat, 29 Apr 1882, p. 3, col. 6.