Irish Emigration – Part 1 : Why They Left

17

17Mar

According to the US Census Bureau, roughly one in ten Americans, or 31.5 million people, claim to have Irish ancestry. And half of all US presidents, including President Biden, can trace part of their ancestry back to Ireland. Those with Irish heritage are spread all over the country, with the highest numbers in the most populated states of California, New York, and Texas. But the top five states with the highest percentage of people with Irish ancestry are, in descending order, New Hampshire (20.2%), Massachusetts (19.8%), Rhode Island (17.6%), Vermont (17.0%), and Maine (16.6%). And although New Jersey as a state didn’t make the top five, the county of Cape May in New Jersey boasts a whopping 30.2% of their residents with Irish blood.

The Irish diaspora reaches beyond America. An estimated 80 million people worldwide claimed Irish descent by the 21st century. Australia has the highest percentage of Irish heritage (30%) outside of Ireland itself. Such a phenomenon begs the question, why was emigration so prevalent among the Irish? A lot of it has to do with its relationship with its neighboring country of England.

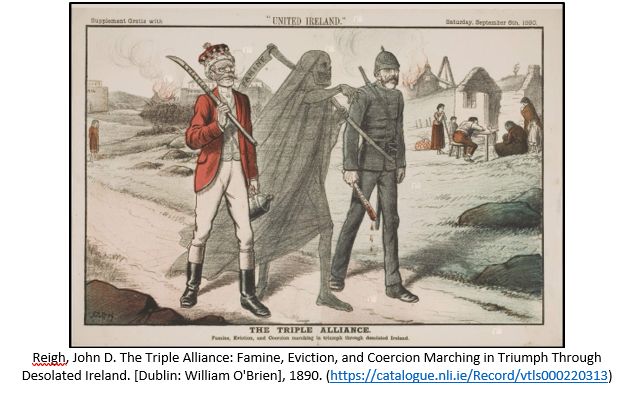

Before Henry VIII split with the Roman Catholic church, Ireland was largely autonomous and was considered to be a papal possession. But in 1541 Henry VIII proclaimed himself the head of the Church of England and King of Ireland. This led to the displacement of Irish Roman Catholic landholders in the 17th century, resulting in even greater English control over the country. As the sectarian conflict increased, Roman Catholics and other non-conforming denominations felt the sting of persecution from Penal Laws which restricted their political and economic opportunities. These discriminatory laws also affected to a certain extent the Scottish Presbyterians who had settled in Ulster from 1609, causing many Scots-Irish to migrate to North America in the latter half of the 18th century. The Penal Laws were mostly repealed by 1793 and by 1801 Ireland became part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, but religious discrimination did not cease with the Act of Union.

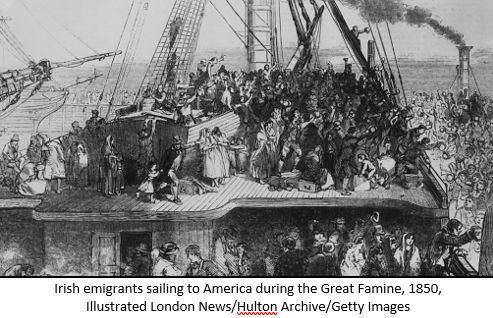

Famine was sadly not an uncommon hardship felt by the Irish. The “Great Frost” from 1739 to 1741 destroyed food reserves and led to poor harvests, resulting in over a quarter of a million deaths. But the worst famine was the Great Famine, or the Potato Famine Blight, from 1845 to 1852 which led to a massive de-population of the country, both from death as well as emigration, as the population dropped by over 2 million. This was felt heaviest in the west country, where Connacht alone lost 30% of its people. Those who left went mainly to Great Britain, with heavy concentrations in Liverpool and Glasgow, while others went to North America. Many went to Canada since British legislation discriminated against United States shipping, keeping the cost of passage prohibitively high. Between 1825 and 1845, 60% of all immigrants to Canada were Irish.

Reasons for emigrating were often a convergence of multiple intolerable circumstances. But there were also economic inducements pulling them to other lands. The scale of emigration, which began as a trickle in 1718 mostly from the north of the country, soon expanded into a torrent by the mid-nineteenth century. Most Irish emigrants fall within one of the following categories: free emigrants, transported prisoners, assisted emigrants, and military personnel.

| Irish Emigrants Sailing To America During the Great Famine |

-

Free Emigrants

Beginning as early as the 1600s, Irish emigrants sought out opportunities in a new land. A small number of Irish colonists were among the first people to travel to the New World and settle in Newfoundland and Virginia. Reasons for emigration were often economically motivated, such as access to land or the various gold rushes in Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and the United States. Others sought to escape religious persecution, poverty, and political oppression. Most of those who left around the time of the American Revolution were Protestants from Ulster, others were Anglicans, Quakers, Methodists, and Baptists.

-

Transported Prisoners

Beginning in 1611 up to 1870, more than 50,000 Irish criminals were deported to a penal colony. This included political prisoners after the Irish Rebellion of 1641, which increased after Cromwell invaded Ireland during the 1640s and 50s. Up until 1775, many of these prisoners were sent to Virginia and Maryland. From 1788 to 1869, over 40,000 were sent to Australia.

-

Assisted Emigrants

Emigration became a heavily managed affair after 1765, and it reached its peak from 1845 to 1855. Qualified emigrants received passage money or land grants as incentives to emigrate. This was an appealing solution to local leaders, who viewed emigration as a way out from providing poor relief from the unemployed and starving masses. Colonies in New Zealand and Australia after 1840 also offered their own financial incentives for emigration to attract much needed skilled workers.

-

Military Personnel

Irish soldiers who served overseas were sometimes offered land to settle in the colony where they served. This was a common practice in Australia from 1791, Canada from 1815, and New Zealand from 1844.

The results of sustained mass emigration have been devastating to Ireland and Northern Ireland. In less than a hundred years, from 1841 to 1926, the population fell by half. And for the migrants themselves, the experience was often mingled with sadness, anger, and even tragedy. Many did not consider themselves as voluntary immigrants, but involuntary exiles escaping persecution, poverty, famine, and other hardships. For America, though, and other heavily settled areas, the results have been largely positive. “The Irish brought labor, skills, capital, and sheer energy to build the farms, cities, industries, and transportation network that laid the foundations of much of America’s prosperity. Indeed, it would be difficult to list briefly the many Irish American contributions to the history of the United States.”

By Emily

Bibliography

US Census Bureau, Happy St. Patrick’s Day to the One Out of 10 Americans Who Claim Irish Ancestry, Written by: Derick Moore, Gerson Vasquez and Ryan Dolan, 16 March 2021 (https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/03/happy-saint-patricks-day-to-one-of-ten-americans-who-claim-irish-ancestry.html: accessed 22 February 2023).

Wikipedia, Irish diaspora, edited 17 February 2023 (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Irish_diaspora: accessed 22 February 2023).

John Grenham, Pre-Famine Emigration (https://www.johngrenham.com/browse/retrieve_text.php?text_contentid=475: accessed 23 February 2023).

FamilySearch Wiki, Ireland Emigration and Immigration, edited 5 December 2022 (https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Ireland_Emigration_and_Immigration: accessed 22 February 2023).

FamilySearch Wiki, Ireland History, edited 8 December 2022 (https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Ireland_History: accessed 14 March 2023).

Kerby Miller and Paul Wagner, Out of Ireland: The Story of Irish Emigration to America. Dublin, Ireland: Robert Rinehart Publishers, 1997.