Learning About U.S. and World History by Exploring Your Family History

19

19Oct

Living History

Living History

Textbooks describe the dates, important figures, and significance of historical events. They detail the concrete facts but it’s people who experience the world changing. Parents and grandparents can describe how events of the twentieth century changed their daily lives, their perspectives and opinions, their work and rest, etc.

The Berlin Wall fell on 9 November 1989; it marked the end of the Cold War and victory over communism. How did that feel for people who lived through a Red Scare and the proxy wars that followed World War II? Was your family affected directly or indirectly?

There are over 100,000 veterans of World War II estimated living in the United States alone; the war ended in 1945 with events still debated today. What was it like to live through?

People around the world watched when human beings first walked on the moon on 20 July 1969 after years of launching rockets and satellites through the atmosphere. Violence erupted in Ireland the same year, a few decades after its independence and many decades after refugees began fleeing to America. There was great advancement and a war in the same year.

The Civil Rights Act was signed on 2 July 1964, a century after the Emancipation Proclamation. South Africa’s Apartheid began in 1948, only a few years after soldiers returned home from war. How was living in 1964 and 1948 different than living 2023?

Gandhi led the Salt March in 1930, revolting against colonial rule of India. Current and former English colonies heard when Queen Elizabeth of England was crowned in 1952. Today’s grandfathers were listening via radio about the Korean War. There were revolutions, coronations, and civil wars in less than a lifetime.

Life Away from the Battlefront

Most countries have a civil or revolutionary war in their history. The American Civil War, for example, spanned four years and many battles. Countless books and documentaries detail army movements, supply chains, soldier casualties, popular opinion, battle dates, etc. Regional and family histories (which are common in North America and Europe) describe individual lives and town activities. Family history research will show what your ancestors were doing while famous battles were fought.

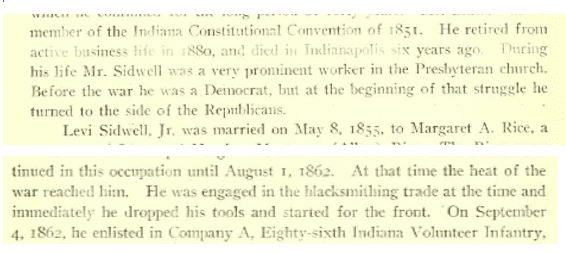

Published genealogies are a useful way to find generations of your ancestors and biographies with varying degrees of detail. A person will often be listed with their birth and death dates, their spouse and children, their parents, and siblings. These genealogies are often included with county histories to show the families that settled and populated the area. For example, a biography will mention if someone returned home from battle with a life-changing injury, volunteered as a soldier and left their town without a blacksmith, or organized a supply drive to support their army. [1] [2]

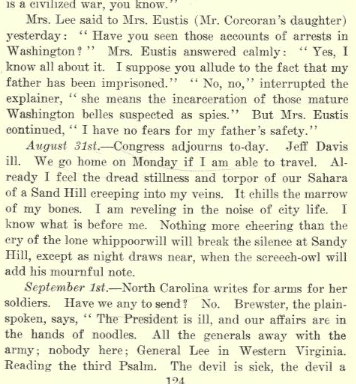

Many people kept journals or diaries that have been preserved for us. The lady of an antebellum Georgia plantation would have recorded rising tensions in the advent of war. Mary Boykin Chestnut’s diary (excerpt pictured) is rather famous. An aging father in Revolutionary New England would have written about his sons fighting in battle, perhaps on opposite sides. If your ancestors did not keep their own record, they may have been mentioned in a friend’s, a relative’s, or a neighbor’s diary. For example, Mary Boykin Chestnut detailed that Mrs. Eustis was the daughter of Mr. Corcoran. [3]

Researching your family history will give context for the wider world that we learn about on the news. Where were they during a noted historical event? What did your ancestors think and how did they react to war? Were they affected by changing boundaries and laws? Did they flee the area or stay as an army approached? How did they participate and how did they live afterward?

Shifting Borders

A country’s external and internal boundaries will have changed many times over its history. As you research your genealogy, you may find that generations of your ancestors lived in one town but were subject to different regional or national governments.

One town might be recorded in different parishes, counties, or countries over the centuries. Sometimes it was because church records used their congregation borders which did not always match political boundaries. More often, a location’s name changed because of war. For example, the Alsace-Lorraine region is located in France now but has historically also been part of Germany. Records will change languages between generations.

Borders often moved over a pre-populated area. The colonial to post-revolutionary eras of North America make a perfect example. Settlements in what would eventually be the United States were generally controlled by England on the east coast, Mexico in the west and very south, and France in the north. Early records in Louisiana, Illinois, and other settlements along the Mississippi River could be in French. English records naturally referenced that country’s monarch before the American Revolution but not after.

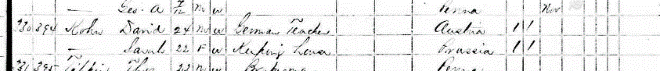

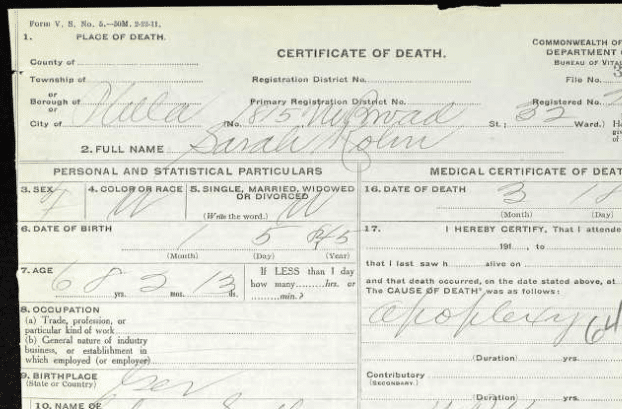

Sometimes it was a more peaceful transition. For example, Prussia once operated as its own country but eventually joined a confederacy of nations that was Germany’s predecessor. It covered a region that is now in northern Germany and Poland. People who were born in the region and later migrated to the United States might switch between “Germany” or “Prussia” when answering questions about their birthplace. One example is Mrs. Sarah Kohn who reported Prussia for her birth country in the 1870 census and Germany for her death certificate. [4] [5]

Exploring your family history will give personal examples to what textbooks teach about war. You can learn how real people were affected by government changes due to war or peace.

Fleeing and Reuniting

People migrate away from or toward something. They might be running from war or following work. The New England colonies of America were created mainly by religious minorities fleeing persecution. The plantation owners of the Caribbean and the French traders of Canada followed economic opportunity. Family crossed continents and oceans in bits and pieces.

Migration usually follows predictable patterns that help in genealogy research. For example, chain migration (when people of a region move to the same destination) shows families and neighbors from Germany settling in areas like early Pennsylvania, which is known for its German heritage. What town someone lived in Pennsylvania may lead to what area in Germany they came from. Another example is the Irish potato famine. Hundreds emigrated from Ireland to the cities and countryside of the United States. If your ancestor immigrated to the United States around 1850, they may have come from Ireland to find work and feed their family.

How do your ancestors reflect migration history? What difficulties were worth leaving their homes? Which opportunities did they follow? Who moved with them? Researching your genealogy will show how historical events affected your ancestors.

These are only a few examples of how exploring your family history will help you learn about United States and world history. Records and genealogies detail how individuals and families lived through all those textbook events. What did your ancestors choose to do while the world changed around them? The genealogical experts at Price Genealogy can help you answer these questions, and many others, as you strive to discover your unique heritage.

By Chloe

Photo: Jack Weir (1928-2005), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

[1] Claybaugh, Joseph. History of Clinton County, Indiana : With historical sketches of representative citizens and genealogical records of many of the old families. Internet Archive. Indianapolis, 1913. https://archive.org/details/historyofclinton02clay/page/106/mode/2up.

[2] Claybaugh, Joseph. History of Clinton County, Indiana : With historical sketches of representative citizens and genealogical records of many of the old families. Internet Archive. Indianapolis, 1913. https://archive.org/details/historyofclinton02clay/page/106/mode/2up.

[3] Chestnut, Mary Boykin. A Diary from Dixie. Internet Archive. New York, 1905. https://archive.org/details/diaryfromdixie00chesrich/page/124/mode/2up.

[4] “1870 United States Federal Census,” database (www.ancestry.com: accessed 25 September 2023), for Sarah Kohn, p. 449, Philadelphia Ward 13 District 39, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

[5] “Pennsylvania, U.S., Death Certificates, 1906-1969,” database (www.ancestry.com: accessed 25 September 2023), for Sarah Kohn, 1913, #33314, Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.