Overcoming Irish Brick Walls – Dates and Ages

7

7Apr

“They’re telling lies again. That crowd were always telling lies.” How often have I heard people say that about their ancestors? It’s not true. How can you lie when you don’t know what’s true or untrue?

We all know that the basic building blocks of genealogy are names, dates and places.

There is one golden rule in genealogy in Ireland. Take nothing for granted. And that means everything you were told, no matter how reliable the information you were given starting off with appears to be—memorial cards, census returns, even birth, death and marriage records—it’s all suspect. Which might seem pretty shocking.

So how do you get anywhere if you can’t trust this basic and most important information?

Let’s start with dates. Most people didn’t keep their own records so they didn’t know how old they were and if asked for their age, they had to guess. If asked for a date of birth, they could only pluck a date out of the air, maybe the day’s date or a special feast or festival. Always be wary of St Patrick’s Day or New Year’s Day although there is at least a 1 in 365 chance that they were born on that day. To make matters worse, most people were older than they thought (rarely younger). Two to five years “out” happened so often that it hardly counted; 10 years “out” was also quite common, and sometimes the difference was 20 years or more—unlikely though this might seem. But searching all available records for the area in question, it is often possible to rule out any others of the same name and prove that it was the person being researched.

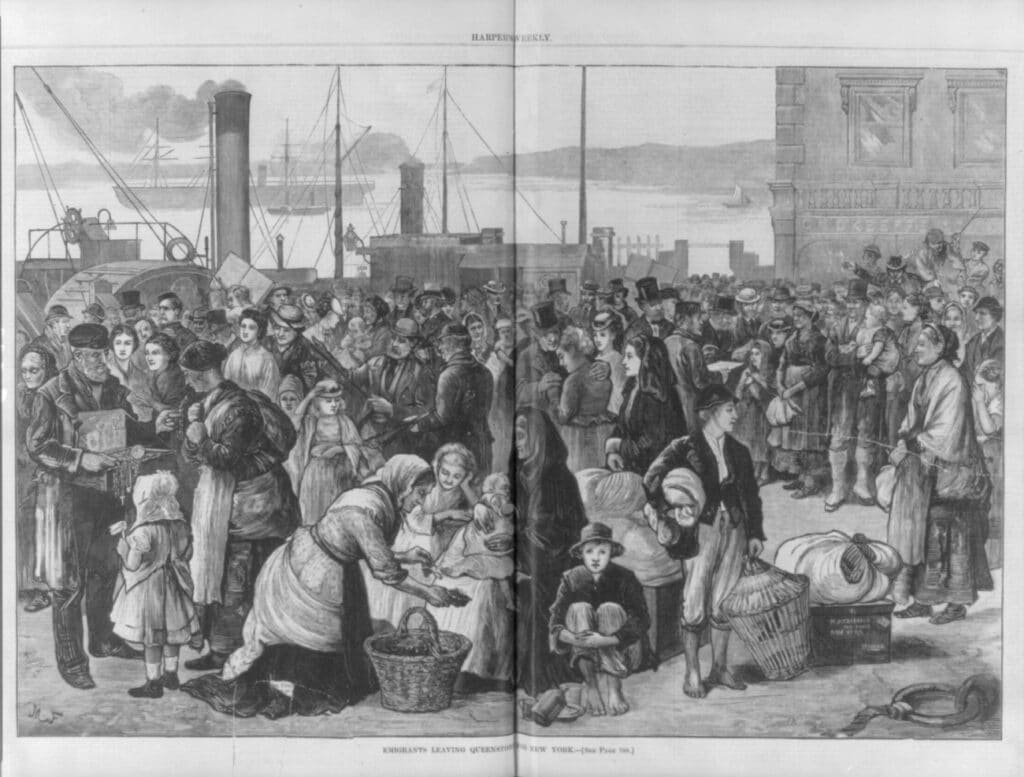

Dates taken from death or burial records are particularly unreliable, especially gravestones. It is not unusual to see that Mr X died in March 1899 and then find him alive (whatever about well and kicking) in the 1901 census. For many families a gravestone was a luxury they could not afford, often depending on the local stone and how suitable it was or not, never mind having to feed the family first.

Dates taken from death or burial records are particularly unreliable, especially gravestones. It is not unusual to see that Mr X died in March 1899 and then find him alive (whatever about well and kicking) in the 1901 census. For many families a gravestone was a luxury they could not afford, often depending on the local stone and how suitable it was or not, never mind having to feed the family first.

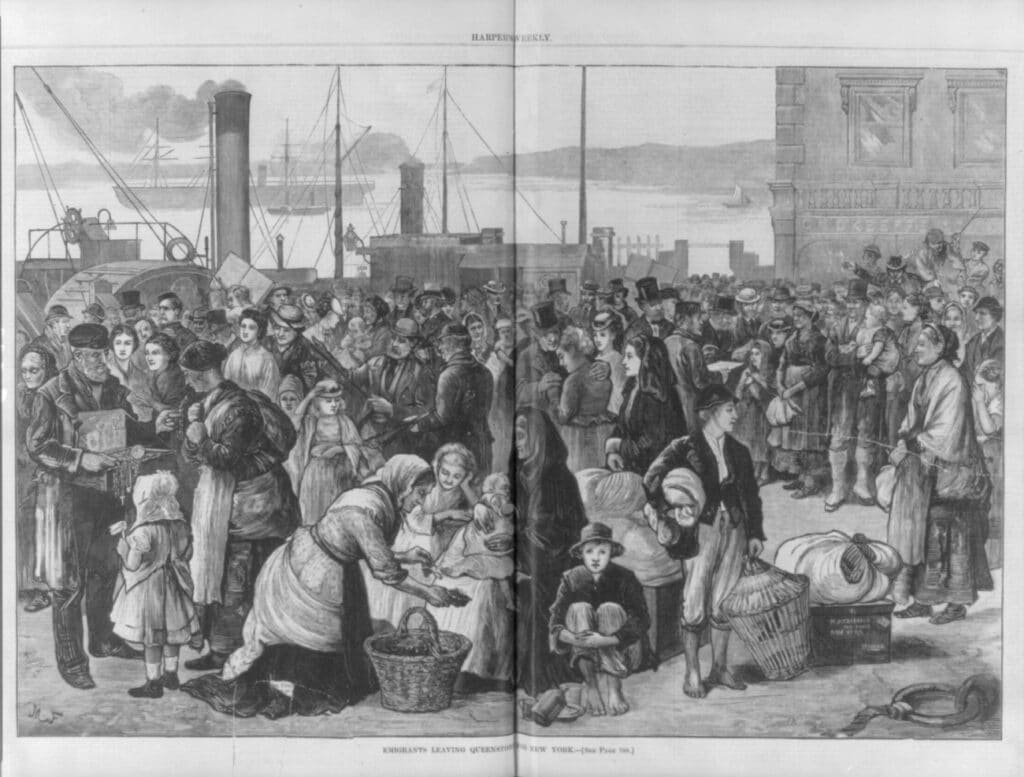

Nearly every family had someone who emigrated. Very often it was the returned emigrant, home for a short visit, who paid for or initiated a family gravestone and the information would be gathered—over kitchen hearths, in pubs and parlours, at weddings, christenings and funerals—the names and approximate dates, the names being more important, argued over and teased out for all those they knew or thought were buried there, the lists painstakingly made out for the local stonemason. The new family gravestone would be erected 20, 30, even 50 years or more after most of those remembered had died so it is inevitable that some mistakes would be made.

It wasn’t that families didn’t commemorate their dead—they did in their own way, and funerals are still a very important part of Irish culture. Most family graves had some kind of a marker whether it was a small stone or metal cross with the family name painted on it—but when the paint wore off it wasn’t always redone, maybe because there was no one left to do that. Even if it was just a small stone at a corner of the grave the family always knew where it was.

In many rural areas there was always someone who knew every grave there. One such example is Riobárd O’Dwyer who knew every stone, marked and unmarked, in every graveyard on the Beara peninsula in West Cork and published several books[1] with not just the gravestone inscriptions but lots of information as well about each family—invaluable when so many families shared just a few surnames and he could even give the nicknames of each family which were so necessary to identify them.

It is not unusual to find many people who appear to have been baptised before they were born but not due to any miracles of science or medicine. Children were baptised when just a few days old or, occasionally, the day they were born. Three months was allowed for the registration of births, marriages and deaths but people were busy working in the fields and didn’t feel any rush to register births. The seasons were more important than the months or days of the week. If people were very late registering births, the local registrar, knowing that they wouldn’t be able to afford the very stiff fines imposed for late registration, would just change the child’s date of birth to fit the registration period. So, the date of baptism is closer to the date of birth than the date on the birth record and many births weren’t registered at all.

My father had two birthdays. Born 13th November, his birth wasn’t registered until 16th February, just outside the period allowed, so his date of birth was registered as 14th December. It was my grandmother’s job to inform the local registrar since my grandfather was a high-ranking policeman during the War of Independence but she was as giddy as he was sensible (opposites attract) so she probably needed to be reminded. Until the 1970s it was even possible to get a passport from one’s baptismal certificate if the birth had not been registered and many had not. But to get a baptismal record, it is necessary to know where the child was baptised.

Unfortunately, many deaths were not registered in the early days of civil registration.[2] If there was property in the family, there was more chance of a death being registered as clear title had to be established before it could be passed on. However, sometimes deaths weren’t registered for several generations which would complicate matters. About 10 years ago, a will was finally probated after about 80 years. The value of the estate amounted to £70 in the 1920-30s but with the legal expenses it would probably have been worthless in today’s money. Fortunately, probate doesn’t usually take so long.

Don’t be fooled by marriage records either. The date of the marriage will be close enough but the age was usually given as “full age.” Most people think this means over 21 but what it really means is that the bride and groom said that they were over 21 which is not the same thing. And in most cases, they probably didn’t know, although there might have been the odd time that they did this deliberately if underage. Many Catholic marriages were not registered as they should have been, even as late as 1905 as the clergy just never got round to it.

Don’t be fooled by marriage records either. The date of the marriage will be close enough but the age was usually given as “full age.” Most people think this means over 21 but what it really means is that the bride and groom said that they were over 21 which is not the same thing. And in most cases, they probably didn’t know, although there might have been the odd time that they did this deliberately if underage. Many Catholic marriages were not registered as they should have been, even as late as 1905 as the clergy just never got round to it.

If people didn’t know how old they were, they wouldn’t be able to give the right information in the census or any other records. Ages in the 1911 census are usually more accurate than in the 1901 census but it’s not unusual to find someone aging 20 years instead of 10, or occasionally trying to get younger instead of older, as well as all the variations in between.[3]

Ages in death records? Yes, they are going to vary hugely too. Beware of round figures like 50 or 60 as they are usually somebody else’s guess and much will depend on how old the dead person looked and acted. Some people are born old while others never seem to age and are always young at heart. All information in death records is second-hand anyway, somebody else’s idea or opinion of the person who died. Irish death records until 2005 give notoriously little information. If the person died in an institution like a hospital, the medical information should be correct but everything else can be wildly incorrect.

A man died in Waterford city in the 1930s. According to the death record, he was of no fixed abode, unmarried and unemployed. An affidavit was attached to it, dated a few weeks after the death was registered, declaring that he was a married man in his 50s, an accountant with an address in Dublin, and signed by his widow. You would wonder what was the story behind that.

So how does one get round all the misinformation and lack of information? If it is a woman and she had children, one can say that she was probably between the ages of 15 and 50 when she had her first and last children. As pointed out, neither party might have been as old as they claimed to be in their marriage record. Or they might have been a lot older, especially women in the census although men could be just as vain about their age. People who were poor generally married younger than those who were better off. They had nothing to lose so why waste time! Those who were better off tended to wait for the right marriage or match but an heiress could be married off very young. Until the 1970s the legal age for marriage was 14 for girls and 16 for boys. Until the 1850s it was the age of puberty for both.

The best advice when searching is to use the age given just as a guideline and be prepared to search at least 10 years, if not 20, on either side.

Happy hunting.

At Price Genealogy we have a team of professional genealogists who conduct ancestry research in Ireland and around the world. We use the latest methods of family history research, including DNA genealogy. We are happy to help you learn more about your family’s heritage and ancestry.

By Rosaleen

[1] Riobárd O’Dwyer Who Were my Ancestors ? Family Trees of Eyeries Parish, pub. 1976, Who Were my Ancestors ? Family Trees of Alihies Parish, pub. 1988, Who Were my Ancestors ? Family Trees of Castletownbere and Bere Island Parishes, pub.1989. All published by K K Stevens Publishing Co., Astoria, Ill.

[2] Civil registration for Protestant marriages started in 1845 and for births, deaths and Roman Catholic marriages in 1864.

[3] Apart from a few “fragments” the only two censuses available are those for 1901 and 1911. Those for 1821 to 1851 were lost in the destruction of the Four Courts complex, which then housed the Public Record Office, during the Civil War in 1922. Those for 1861 to 1891 were pulped to recycle paper during World War 1 without realising that the information they contained had not been abstracted as it was in the rest of Britain.

Introductory picture: Miscellaneous Items in High Demand, PPOC, Library of Congress, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Emigrants_leaving_Queenstown_(Ireland)_for_New_York_LCCN2004678776.jpg

Cemetery photo:Knighton Old Cemetery by Bill Boaden, CC BY-SA 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Knighton_Old_Cemetery_-_geograph.org.uk_-_5511127.jpg