Panning for Gold: A Case Study in American Probate Records

3

3Jan

American Probate Records: A Potential Goldmine

American Probate Records are a staple in United States genealogy research, and for good reason. Processing an individual’s probate could take years, which could produce dozens of records about entire family groups. Additionally, probate records frequently include information about the women in a family long before censuses listed each family members’ name. Probate records are also extremely helpful for working to establish an ancestor’s FAN (Friends, Associates, and Neighbors) network, which can provide numerous clues into their lifestyle and identity.

Even for a beginning researcher, probate records can be invaluable sources of information, but there is one small consideration that often results in these records not being fully utilized: probate records can be very time consuming! They can be hard to locate, hard to read, and hard to understand. It’s true—sometimes you will spend hours and hours searching for and reading through a set of probate records and come out with very little helpful information. But every so often you’ll come across a few “gold nuggets” that will make all of the time and effort worth it! And rest assured that all of us researchers here at Price Genealogy will happily invest that time for you so that you can benefit from all your ancestors’ probate records have to offer.

An Introduction to American Probate Records

In terms of genealogical records, the word probate refers to any record created after a person dies in relation to their estate or belongings being dispersed. These records are generally created at the county level, though the court and organization methods each county used varied greatly.

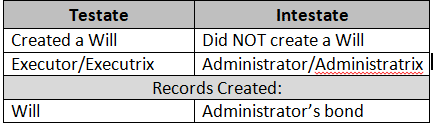

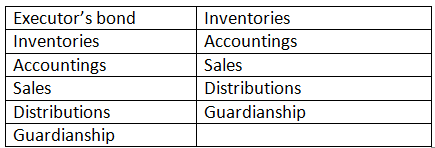

Regardless of how the records are organized in each location, all probate records can be classified by one important factor: whether or not the deceased individual left a will. If a will was created, the individual was referred to as having died testate, and that word will show up throughout the records. If no will was created, the individual died intestate.

Though the phrases used in each scenario are different, other than the presence of a last will and testament, there are no major differences in the types of records created. Many researchers are frustrated if they discover that their ancestor did not create a will before they died, but in reality, the other records created during the probate process are often just as beneficial (if not more so!) than an actual will! Listed below are the differences between testate and intestate probate proceedings and the types of records you can expect to see in each scenario.

Now that we know a little bit more about why probate records are valuable and how to understand them, let’s look at an example of just how essential probate records can be in genealogy!

American Probate Records Case Study: Rebecca H. Kennerly

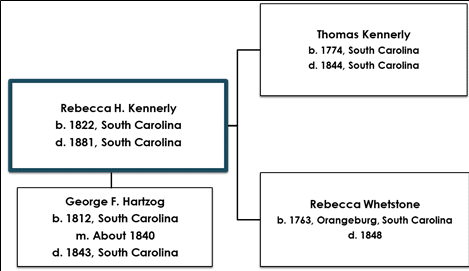

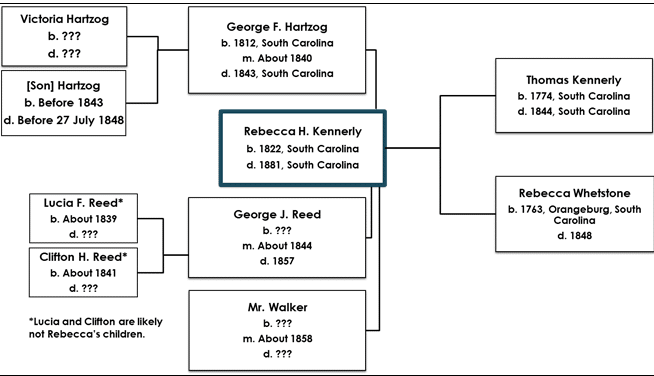

Rebecca H. Kennerly was born in 1822 in South Carolina to Thomas and Rebecca Whetstone Kennerly. Sometime around 1840, she married George F. Hartzog, likely in South Carolina as well. George Hartzog died just a few years after they were married, and Rebecca died decades later in 1881.

The pedigree below represents all of the information that was known about Rebecca before any research began, but keep reading and you’ll find out just how much “gold” we dug up about Rebecca by researching just in probate records!

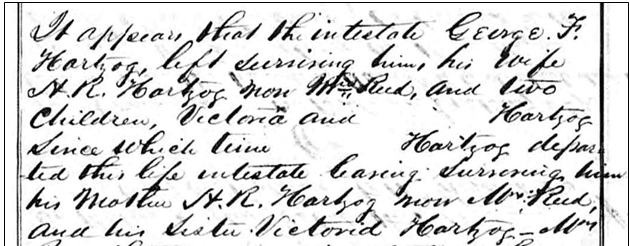

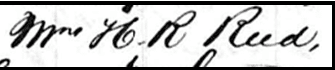

First, we found George F. Hartzog’s probate records to see what information might be included about his wife, Rebecca. George died intestate, and his estate records were probated in Barnwell County, South Carolina between October 1843 and January 1852—almost a decade.[1] While reading through the records we noticed that George’s widow’s name went from “Mrs. H.R. Hartzog” to “Mrs. H.R. Reed.”

Sure enough, in a note written before 8 January 1845, we found the phrase, “The Widow having lately inter-married with a Mr. George Reed.” Prior to searching George Hartzog’s probate records, there was no indication that Rebecca H. Kennerly had married again! What a great find!

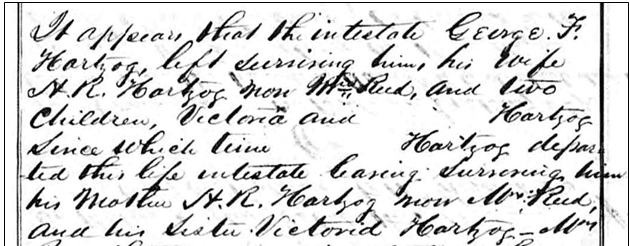

But the surprises didn’t stop there. Because George Hartzog died intestate (didn’t leave a will), his estate was distributed between his heirs at law. An heir at law is someone who, by blood or marital relation to the deceased, has a legal right to inherit property. This is usually a spouse and children, but can include siblings and parents as well.

In George’s probate records, a note dated 27 July 1848 detailed the interesting scenario regarding George Hartzog’s heirs at law. Apparently, George left surviving him his wife, a daughter Victoria, and an unnamed son; each was due a portion of George’s estate. Prior to the note being written however, George and Rebecca’s unnamed son died (likely in infancy, as he never had a name). The son’s portion of the estate was to be split between Rebecca and Victoria, but legally, the portion needed to have been recorded as first belonging to George’s son. This record was the first ever indication that Rebecca H. Kennerly and George F. Hartzog had any children! And though Victoria may have been discovered in other records down the road, it is extremely unlikely that George and Rebecca’s unnamed son would have been mentioned anywhere else.

After having such great success in reading through Rebecca’s first husband George F. Hartzog’s probate records, we turned to the probate records of her second husband, George Reed, to see what other “gold nuggets” we could unearth.

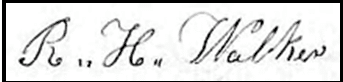

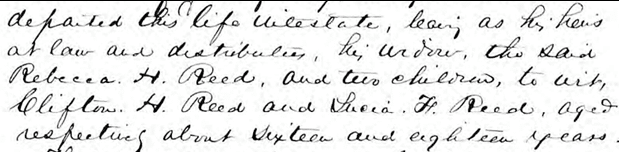

George J. Reed also died intestate in Barnwell County, South Carolina. His estate was probated in that county between July 1857 and January 1859.[2] Remarkably, we found almost the exact same scenario as we first found in George F. Hartzog’s probate records! Rebecca H. Kennerly was made the administratrix of George Reed’s estate under the name Rebecca H. Reed. A year and a half later though, she settled the probate account under another married name, R. H. Walker! Rebecca had once again married in the middle of her deceased husband’s probate records.

Further reading in George Reed’s probate records led to information about his own heirs at law: his widow, Rebecca, and two children, Clifton H. Reed and Lucia F. Reed. Included in the records were Clifton and Lucia’s ages—16 and 18 respectively. Because we have an estimated marriage date of Rebecca and George Reed derived from George Hartzog’s probate records (about 1844), we can say that Clifton and Lucia were likely not Rebecca’s biological children (as they were born about 1839 and 1841).

Looking back at the pedigree included above, we see that prior to searching through any probate records, very little was known about Rebecca H. Kennerly—just some basic information on her and her parents, and that she was married once. But after researching in only 2 probate files, we discovered so much! It turns out that Rebecca had two children with her first husband (one of whom died nearly the same time has her husband), she was actually married at least 3 times, and helped raise two step-children!

Yes, digging through the American probate records did take some time, and yes, reading through every page took even more time than that. But as evidenced by the treasure trove of information found within them, probate records are definitely worth it!

Amy

[1] “South Carolina probate records, files and loose papers, 1732-1964,” Barnwell County, Probate court, digital images, FamilySearch (http://familysearch.org : accessed November 2019); Probate Case 85, package 5, George F. Hartzog.

[2] “South Carolina probate records, files and loose papers, 1732-1964,” Barnwell County, Probate court, digital images, FamilySearch (http://familysearch.org : accessed November 2019); Probate Case 133, package 12, George J. Reed.