Research in an Urban Setting

16

16Aug

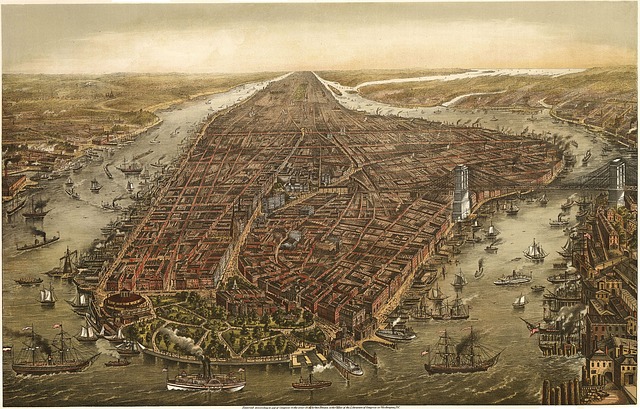

The process of doing family history research in a large urban area, including its suburbs, can be quite a challenge. In areas with large populations, each collection can have numerous records to sift through, and there may be a greater variety of potentially useful types of records. One city can be divided into many parishes, wards, precincts, or sub-communities. Due to the common practice of stating the largest nearby city as one’s place of origin, it may be necessary to even look at multiple neighboring communities. Collections can be housed at either the city or county level, or both, depending on the record. If you look at a map of the population distribution of the United States,[1] the coastal areas, including the North Coast/Great Lakes region, are the most densely populated. These areas often require special knowledge and skill with city research.

The key to maximizing your research efforts in densely packed urban areas is to know what exists and where the records are held. Frequently, a record of one event can be located in multiple collections. For example, the New York City Department of Health, the New York City Clerk’s office, and a church--if married by a minister, would each hold records related to the marriage of a New York City couple in the early 20th century. Each of these records often contains slightly different information. One might only give the country of birth, while another may give the exact town of birth for the bride and groom. One record may give witnesses and their addresses, and another may give ages and occupations. Although this duplicate recording of events is true for research in most regions, city research adds that one extra level of government that brings many more unique record collections.

Generally, the court and clerk’s offices would be where the legal documents of a person are held, or at least generated. Some may be in a city or town hall, a city or county archive, a health department, or may even be archived in a library or historical society. Government records include: probate records, tax records, land records, naturalization records, and vital records. Beyond these typical records, cities will have their own special collections related to city employment, schools, welfare, petitions, elections, military activity, jails and law enforcement, etc. Each of these government-generated records can be held at a different location or in multiple locations, depending on the time-period and the city. For example, Chicago’s Daley Center skyscraper houses a vital records office, a county court, and a separate county court archive. New York City, Philadelphia, and Baltimore all have city archives. In New York City, the municipal archives is located in the Surrogate’s Court building, across from Tweed Courthouse and the City Hall. There is also a branch of the National Archives in New York City that will be of use to those researching city ancestors, that holds records such as naturalizations that took place through federal courts from 1906 forward. The Baltimore City Archives, on the other hand, is currently located in a dilapidated neighborhood outside of walking distance to any other archive. City records will also often be located within state agencies, especially state archives, even when a city archive exists.

Church records remain an important genealogical source for urban research, as they are for any research. From the early days of American settlement, most churches have kept records of their members. Depending on the denomination, their archives not only include vital records, but congregation rosters, which may include admissions into and departures out of the parish. Many had yearbooks, which include pictures of their parishioners, and which list the leaders of the congregation. One complication of city research is that there are often many more parishes from which to choose that might have been the one your ancestor attended. Identifying your ancestor’s specific address from a census, city directory, or other record can help narrow down which churches they were most likely to have attended. In our previous article, “Adding Branches With Church Records,” the necessary steps to locate the records of a family were explained, which of course, also applies to urban areas.

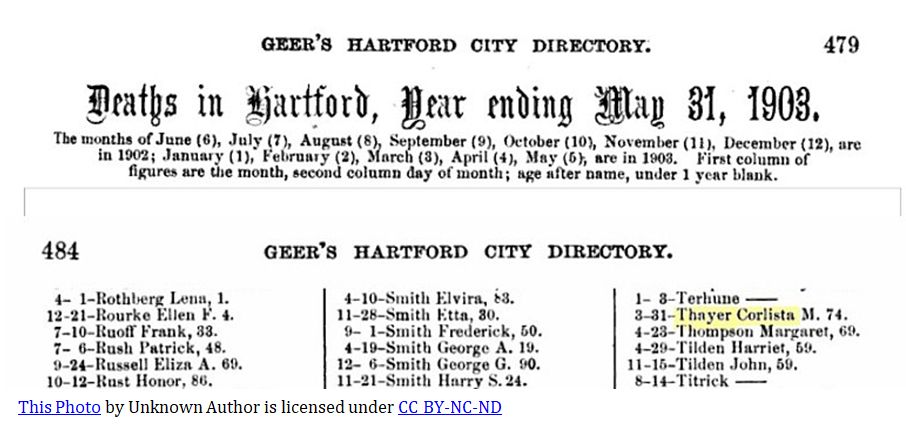

City directories, though originally published for contemporary commercial purposes, greatly benefit genealogical research in cities. It is a good thing too, for without them city research would be even more difficult. Individuals and families in an urban setting tend to move more frequently than those settled in country life. There also tend to be more persons that go by the same name. The city directories provide the ability to track heads of households and working men from year to year, identifying by year any changes in their address or occupation, as well as other working men listed at the same address. Although not directly stated in city directories, your focused use of these directories can reveal evidence of family groups, death or migration, separation or divorce, etc.

There are many places to visit in urban areas that can help with one’s research. Cities are usually broken down into smaller subdivisions, such as wards or neighborhoods, and each may have a local library. The library might have copies of neighborhood historical newspapers on file (such as the Brooklyn Eagle, a paper that primarily covered that neighborhood), or an atlas or map with old references. These would show how the area grew over the years. It might also house city directoies of the area or old telephone books. Each of these add sources for the researcher to glean information about the person being researched. These neighborhoods, with great civic pride, may also be home to a local historical society. An example is The Preservation Society of Fells Point, Baltimore, which manages a visitor center in the historic neighborhood. These contain pictures and stories, and may offer seminars that chronicle the history of the area. Ethnic “clubs,” with names like Bohemian Hall, the Sons of Italy, and the German-Hungarian Club, may also be local sources of information in an urban area. Ethnic newspapers are also common to urban areas, such as Polish newspapers in Chicago, or German and African American newspapers in Baltimore.

For those with urban ancestry, a lot can be seen in a visit of just one or two days. On one occasion, one of the authors visited the Queens courthouse in Jamaica, and obtained the naturalization record of his great-grandfather. He then visited Flushing Cemetery to take a picture of the man’s headstone. After this, the author went to the New York City archives in Manhattan to order a copy of a birth certificate. Later that day, he visited another grave at Calvary Cemetery, in Long Island City, as well as the local church to look for a Holy Communion record of his ancestor. The other writer of this posting has taken day trips to Baltimore, Philadelphia, New York, Boston, Washington D.C., and Chicago, among other cities. These trips were filled with visits to city archives, courthouses, cemeteries, churches, and other interesting landmarks.

Urban research presents its own unique challenges (e.g. population density, migration frequency, manuscript quantity and variety), but also an additional layer of possibilities such as city-specific record types, an abundance of ethnic or community records and organizations, as well as archives and research projects that have been given significant funding. Our researchers at Price Genealogy stand ready to help with your city research needs. Contact us today.

Paul and Michael

[1]“Population Distribution,” World Maps (https://wiki--travel.com/detail/population-map-us-2.html : accessed 28 June 2019).