Resurrecting Thomas Edwards – Using Probate Records to Resolve Conflicting Evidence

23

23Aug

What happens when the perfect baptism record and family is found, but further research suggests that the person actually died as a child? Read on…

Thomas Edwards was buried on 7 October 1827 at age 50 in Woodstock, Oxfordshire, which suggests that he was born about 1777. He married Mary Harris on 1 October 1807 at St. Giles, Oxford, a parish seven miles from their home, which is where they would have their children and where Thomas died. Thomas was a farrier—a craftsman skilled with shoeing all types of horses and “devising corrective measure to compensate for faulty limb action.” A farrier was not a blacksmith, but required training in blacksmithing in order to properly fit the shoe. Thomas Edwards’ occupation was a unique identifier, which definitively linked him to the baptism and marriage records of his children.

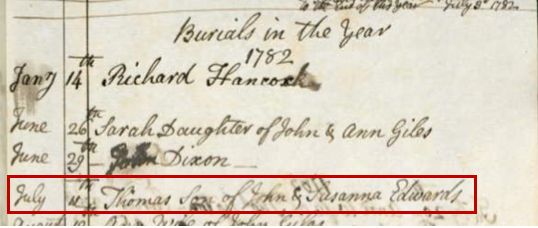

The search for Thomas’ parents began in Shenington, Oxfordshire, a village some 20 miles north of Woodstock. Prior research revealed that Thomas’ wife, Mary Harris, was baptized at Shenington in 1782. It was also found that two brothers-in-law were blacksmiths and one was a farrier, all of whom lived in Shenington. All clues pointed to Shenington, and conveniently, a baptism record for Thomas Edwards was found there. He was christened on 26 December 1777, the son of John and Susannah Edwards. Baptismal records for two additional sons were found: James in 1779, and John in 1782. Inconveniently, however, a burial record was found for Thomas in 1782!

Clearly, if this Thomas died in 1782, he could not be the same Thomas who died in 1827. However, what if the record was wrong? It wouldn’t be the first time a clerk made a mistake, and this clerk seemed to be particularly sloppy when it came to vital records. Every other fact supported this Thomas Edwards as the ancestor: the baptism fit the expected birth year, the location matched his wife’s birthplace, Thomas named his eldest son John, and a daughter was named Susannah (the same names as the parents on his proposed baptism record). In addition, the ancestor’s occupation was similar to his wife’s brother’s occupations, and they may have trained together. A theory developed; what if the burial entry was actually for John Edwards, the brother who was baptized in January 1782, just seven months earlier? Proving this theory began by searching for evidence of an adult John Edwards. No records were found for John, though the name is fairly common, and a lack of records alone is not enough to dismiss the burial record as incorrect.

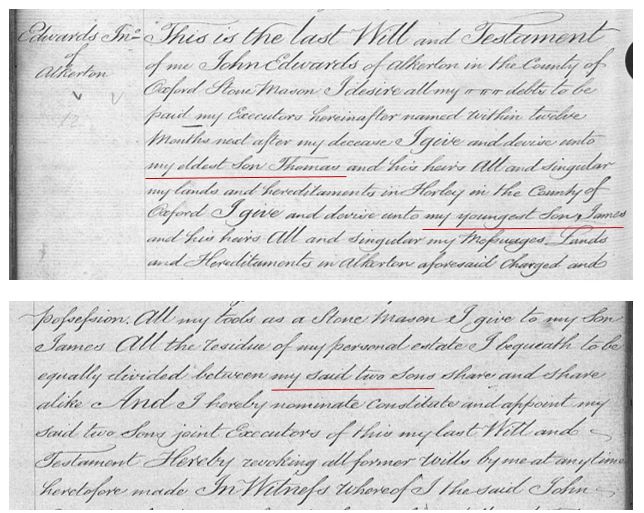

The necessary positive proof was found in the will of John Edwards, a stonemason of Alkerton (a small hamlet within the parish of Shenington). Dated 6 September 1827, it named his eldest son as Thomas, and his youngest son as James.

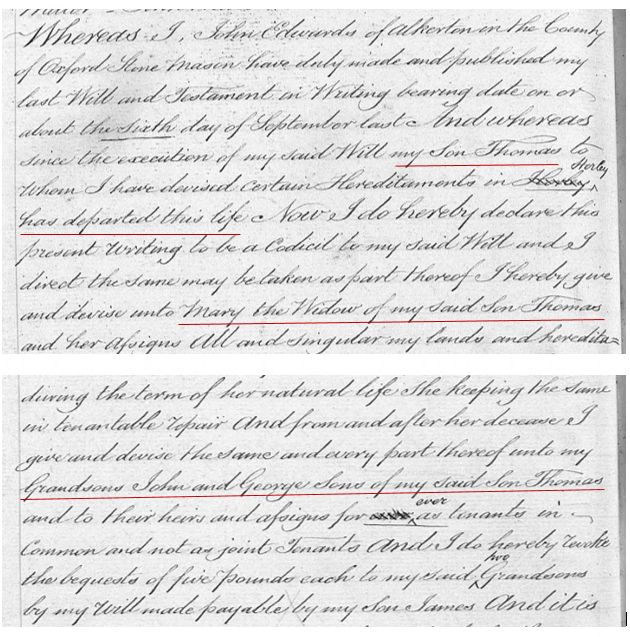

No mention was made of John’s wife, Susannah, nor of their youngest son, John. In fact, John specifically named as his youngest son, James, strongly suggesting that his son John, who was baptized after James, was dead. The parish register was searched, but no burial record for John was found, further evidence that the theory was plausible. What of Susannah? A quick search located a burial record for her at Shenington in 1822. John Edwards’ will neatly wrapped up all the conflicting evidence into a nice little box, but he didn’t stop there. John provided a codicil to his will, dated 9 October 1827, just two days after his son was buried. In it, he stated that “since the execution of my said Will my son Thomas…has departed this life.” He went on to name his son’s widow, Mary, and his two grandsons, John and George, all of which matched the facts regarding the ancestor.

A reasonably exhaustive search was conducted for another burial for Thomas Edwards in 1827, but none was found, proving that Thomas Edwards of Woodstock was the same Thomas Edwards named in the will of John Edwards. A reasonably exhaustive search did not find an adult John Edwards of the correct age in Oxfordshire. Since there was no mention of him in the will of the elder John Edwards, it is very likely that he was the child that died in 1782, and not Thomas.

Since all of the facts regarding Thomas Edwards of Woodstock matched the facts regarding Thomas Edwards (the son of John and Susannah Edwards), and since the only conflicting evidence was the burial record of a child named Thomas Edwards, it was concluded that the two men were one and the same, essentially “resurrecting” Thomas Edwards.

Probate records are a frequently underutilized resource for determining relationships. It is estimated that ten percent of the population left a will, but upwards of 25 percent of the population were named in the wills of others. Even when there is no will, the letters of administration will often name the next of kin, either the widow (the “relict”) or the eldest son. Always check for probate records!

Julie