Revolutionary War – Part 1

7

7Jul

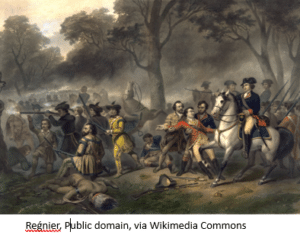

Every year on Independence day, many Americans make plans to barbecue and watch fireworks. But do we think about why this holiday exists? We are celebrating the birth of our country, and some of us had ancestors who participated in that by fighting in the Revolutionary War. What better way to celebrate our country’s independence than learning about these ancestors and the history of that time?

Every year on Independence day, many Americans make plans to barbecue and watch fireworks. But do we think about why this holiday exists? We are celebrating the birth of our country, and some of us had ancestors who participated in that by fighting in the Revolutionary War. What better way to celebrate our country’s independence than learning about these ancestors and the history of that time?

Leading up to the war

The Revolution era of the U.S. began after the French and Indian War, which ended in 1763 with the Treaty of Paris. Until this point, the colonists were content to be British citizens. However, the king of England had accrued debts in the war and needed to pay them off. The colonists didn’t like what he did in that attempt. [i]

The king had offered bounty land for the war, but it was in a closed-off area, so veterans couldn’t claim this land that was supposed to be theirs. Only Virginians got land from the Kentucky land office. Later this land was given to the Province of Quebec through the Quebec Act of 1774.

Over the next several years, the king proceeded to pass many acts to tax the colonies. This included the Sugar Act (1764), which prevented Boston from importing luxury goods. The Currency Act (1764) meant they could only get money from the government, so many colonists began smuggling. The Virginia General Assembly responded to the Stamp Act (1765) by creating the Virginia Resolves in 1765, which included everyone having the same rights as if they were in Great Britain, with no unbearable taxes, and no taxes without consent. The Sons of Liberty were established by Samuel Adams that same year. Parliament repealed the Stamp Act in 1766.

The Declaratory Act (1767) was passed to prevent colonial assemblies from being able to pass any binding law, thus increasing control by the Crown. The Townshend Acts (1767) were passed the following year to raise revenue and establish the Crown’s right to tax the colonies. After the Boston Massacre (1770), these acts were repealed except for the Tea Act (1773).

Things started to get more tense in the 1770s. In 1771, the battle of Alamance took place, where North Carolina citizens took up arms against colonial officials. They wanted an honest government and reduced taxes. The next year, the Sons of Liberty from Rhode Island looted and burned a ship.

In 1773, the colonies formed committees at town and county levels in response to the Virginia House of Burgesses’ proposal that each colonial legislature appoint a standing committee for intercolonial correspondence.

A famous event from the early 1770s was the Boston Tea Party. This was in response to the Tea Act of 1773, which only allowed colonists to buy tea from the East India Company. Most of the other colonies also had their own tea parties that year and the next. Some dumped the tea into the sea or rivers. Some held onto the tea to sell to France later. Some forced the ships bringing in tea to go back to England. Many colonists boycotted tea.

The crown continued passing acts, and the colonists continued responding to these acts. The Intolerable acts and the Quebec Act were passed in 1774. The Intolerable Acts included closing Boston port, which was the largest port at the time; removing the Massachusetts government Charter; the Administration of Justice Act (1774), which required all trials to happen in Great Britain; and an expansion of the previous Quartering Act (1774). In addition to granting land to the Province of Quebec, the Quebec Act also stripped colonies of their elected assemblies. It restored the Catholic Church’s right to impose tithes, which wouldn’t be taken so well in predominately protestant colonies.

The Powder Alarm also occurred in 1774. Militia companies were called to resist British troops who were sent out to capture ammunition stores. But the British had already done so by the time the militia was ready. A few days later, the first Continental Congress was formed. A month later, they made the Declaration and Resolves (1774), and the Declaration of Rights and Grievances. They also prohibited trade with Great Britain.

Battles and skirmishes began happening before total war broke out. Lord Dunmore’s War occurred in Virginia in the fall of 1774. In the spring of 1775 was Patrick Henry’s “Give me liberty or give me death” speech, as well as Paul Revere’s and William Dawes’ rides. Next, British soldiers engaged with colonial minutemen at Lexington and Concord.

[ii] Some books to read about this era are Boston, the Red Coats, and the Homespun Patriots 1766-1775 by Armand Francis Lucier—this book is a collection of newspaper accounts of what was going on in Boston; and Reluctant Break with Britain: From Stamp Act to Bunker Hill by Gregory T Edgar.

Some books to read about this era are Boston, the Red Coats, and the Homespun Patriots 1766-1775 by Armand Francis Lucier—this book is a collection of newspaper accounts of what was going on in Boston; and Reluctant Break with Britain: From Stamp Act to Bunker Hill by Gregory T Edgar.

The Revolutionary War

The Revolutionary War was three-sided. On the Patriots’ side were French and Spanish allies. On the British side were Hessian mercenaries from Germany, and Loyalists—colonists who remained loyal to the king. The third side was the neutral party: pacifists, Quakers, Amish, Mennonites, and Anabaptists, who just wanted to stay out of the way.

All men on the Patriot side were militia unless disabled or otherwise legally exempt. Colonial laws determined who could be exempt. Some colonies allowed men to send in substitutes. Most servicemen were free males between the ages of eighteen and sixty. Those older than forty-five rarely left their states. The Patriots were armed and prepared. Thanks to the French and Indian War, most colonists owned flintlock guns.

The Continental Army was divided into brigades, which were divided into regiments, which were divided into companies. The companies were organized at the town and county levels. This meant that neighbors served alongside each other. At the beginning of the war, there were two to three regiments per brigade and ten companies per regiment. Due to consolidation during the war, regiments ended up with two to three companies by the war’s end.

Patriots also included state troops and minutemen. Minutemen could be ready to fight at a minute’s notice. They were paid volunteers organized by companies and drilled every week.

There were also county militias, which mainly served within their own state or county boundaries. County militiamen were unpaid. If anyone in the county militia had to leave their county for duty for over 30 days, they were paid by the state. Further, they were paid by the Continental Congress if they had to leave the state.

As for the loyalists who supported the king, most were forced to leave their homes during and after the war. Some went to England, and others went to Canada. Some of the Germans who served on the British side stayed in North America, mainly in French Canada. [iii]

Forgotten Patriots

Some Patriots and Loyalists who served in the Revolutionary War were African Americans and Native Americans. These people are sometimes known as the forgotten Patriots due to the systematic, historical racism and bias that have buried their records.

Six to nine thousand African Americans served on the Patriot side, and up to 20,000 fought on the British side. After the war, Britain sent their black soldiers to Canada, the Caribbean, and the British Isles as free men.

Many of the colored troops stayed at the rank of private. Their roles included general laborers and cooks; infantry and artillery men; sailors and ship pilots; spies, scouts, and couriers; and drummers and fifers.

The first Rhode Island Regiment, formed in 1778, was known as the “black regiment.” This regiment consisted of 225 men, 140 of whom were African Americans. This was the largest percentage of black people in an integrated military unit during the American Revolution. The enslaved men in this regiment were promised freedom.

Women also participated, including African American women. Enslaved women fled slavery during the war, desiring freedom for themselves and their children. A breakdown in oversight and state authority also helped these women run away. Women’s participation also included boycotting British goods, producing goods for soldiers, and spying. Some women even disguised themselves as men so they could fight.

The next blog in this series will review how this history affects our genealogical research on these ancestors.

Katie

Resources

- https://familytreewebinars.com/webinar/u-s-revolutionary-war-a-case-study-approach/?category=records&subcategory=military&subsubcategory=revolutionarywar

- https://familytreewebinars.com/webinar/remote-research-in-the-databases-of-the-daughters-of-the-american-revolution-genealogical-research-system/?category=records&subcategory=military&subsubcategory=revolutionarywar

- https://familytreewebinars.com/webinar/revolutionary-war-series-1-of-5-the-revolution-more-than-just-the-war/?category=records&subcategory=military&subsubcategory=revolutionarywar

- https://familytreewebinars.com/webinar/revolutionary-war-series-2-of-5-the-participants-in-the-war/?category=records&subcategory=military&subsubcategory=revolutionarywar

- https://familytreewebinars.com/webinar/revolutionary-war-series-3-of-5-records-created-by-the-revolutionary-war-during-the-war/?category=records&subcategory=military&subsubcategory=revolutionarywar

- https://familytreewebinars.com/webinar/revolutionary-war-series-5-of-5-records-created-by-the-revolutionary-war- after-the-war-bounty-land/?category=records&subcategory=military&subsubcategory=revolutionarywar&sortby=newest

- https://www.familysearch.org/rootstech/session/remembering-the-black-patriots-of-the-american-revolutionary-war

- https://www.familysearch.org/rootstech/session/african-americans-in-the-revolutionary-war-war-of-1812

[i] "Revolutionary War" by Conal Gallagher is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

[ii] "Soldier of the American Revolutionary War" by EraPhernalia Vintage . . . [''playin' hook-y''] ;o is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

[iii] "Redcoats & Rebels Revolutionary War Reenactment" by leewrightonflickr is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.