Royal Navy – Part 2, Ordinary Sailor (Ratings)

10

10Jun

In our research of British families, we often encounter service in the military—the British Army, the Royal Navy (including the Royal Marines), the Merchant Navy, as well as the East India Company’s army and navy. Many British families had one or more people who “went to sea.” The records of the Royal Navy alone are vast, but this really should not be surprising since it had a global reach and was the foundation upon which British worldwide influence rested for so long. In part 2 of our examination of sources for our Royal Navy ancestors, we will look at the best records for regular seamen and consider a case study of a Royal Navy “rating.” Finally, finding aids for ratings and other naval topics will be reviewed. As with part 1, a few selected resources are bolded.

Royal Navy ratings

Regular sailors were “rated” according to the skill level and specific tasks that they could do. They would start out as a landsman (later called an apprentice seaman), then with some experience become an “ordinary seaman,” then an “able seaman/able rate” and “leading rate.” It was not common, but some could become midshipmen and then perhaps pass the examination to become a warrant officer or commissioned officer. But, for most ratings, the next steps would be to petty officer, chief petty officer, and quartermaster. Most sailors never advanced beyond “able seaman.”

Naval ranks can be confusing since there were official rank titles, temporary ranks by assignment, informal positions under certain circumstances, and social distinctions between gentlemen and non-gentlemen. Many sailors were forcibly “impressed” by “press gangs,” and as such were often treated as landsmen.

Naval ranks can be confusing since there were official rank titles, temporary ranks by assignment, informal positions under certain circumstances, and social distinctions between gentlemen and non-gentlemen. Many sailors were forcibly “impressed” by “press gangs,” and as such were often treated as landsmen.

Boys as young as 8 or 12 could be servants on board, which was the lowest position. Boys could become “cabin boys,” “powder monkeys,” and if they were from gentry stock, they could be an “officer’s servant,” which would put them in position to be a midshipman on a pathway to commissioned officer rank. Among the seamen were members of the carpenters’ crew and quarter gunners. Petty officers included quartermasters’ mates, sailmakers’ mates, caulkers’ mates, gunners’ mates, armorers’ mates, watch captains, coopers, coxswains, yeomen, sailmakers, masters-at-arms, caulkers, ropemakers, armorers, full carpenters, boatswains, and gunners.[1]

It can be a challenge to trace the careers of naval ratings. Until 1853, there was no consistent system of tracing the service of men over their whole career. They signed onto a ship for the duration of its voyage and then had to find another ship to join. Many men moved back and forth between the Merchant Marine and the Royal Navy, so it may be possible to find them in Merchant Marine records, which become more useful beginning in 1835.

Prior to 1853, it is important to learn the name of at least one of the ships a man served on. If this is discovered, and the information is correct, there is a strong chance that you will find your seaman in the ship’s muster rolls (ADM 3l6-41, 115, 119) and pay books (ADM 31-35, 117). From here, the usual strategy is to move forward and backward through these lists to the beginning and end of the man’s career. The very first entry may give his birth place and his age. This takes a lot of time, but the end result is rewarding. If your sailor allotted part of his wages to his wife, parents, or other dependents, then there should be a record of this in the Allotment Registers (ADM 27). Also, if he received a pension, a summary of the vessels he served on may be part of a Certificate of Service (ADM 29) prepared by the Pay Office for the Greenwich Hospital, which provided support for in-pensioners and out-pensioners. Pensions were first granted in 1859 for all ratings who had served continuously for twenty years.

There are other strategies if you know a port or location of a sailor, at a particular time (ADM 7, 8). If he died in service or in battle, or was in the Battle of Trafalgar (1805), there is hope. Names of ships may be found in church christening, marriage and burial records, commonly located in ports where ships were based. One of the experts on naval sources is Bruno Pappalardo, who provided a detailed analysis of a seaman named John Bray, gunner, who left the service in 1836 and was accepted by the Greenwich Hospital as an out-pensioner. His career was traced back to the beginning in 1818. His marriage date and wife’s name were discovered, and details of his family were learned. See Pappalardo’s book, Tracing Your Naval Ancestors.[2]

There are other strategies if you know a port or location of a sailor, at a particular time (ADM 7, 8). If he died in service or in battle, or was in the Battle of Trafalgar (1805), there is hope. Names of ships may be found in church christening, marriage and burial records, commonly located in ports where ships were based. One of the experts on naval sources is Bruno Pappalardo, who provided a detailed analysis of a seaman named John Bray, gunner, who left the service in 1836 and was accepted by the Greenwich Hospital as an out-pensioner. His career was traced back to the beginning in 1818. His marriage date and wife’s name were discovered, and details of his family were learned. See Pappalardo’s book, Tracing Your Naval Ancestors.[2]

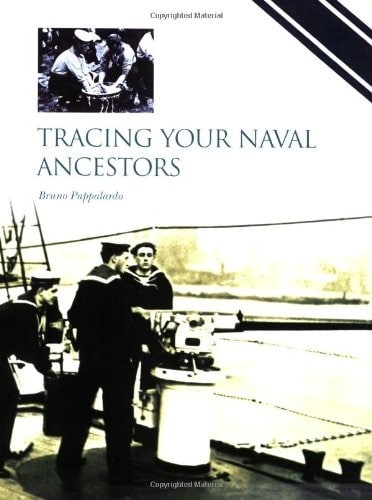

Beginning in 1853, the Admiralty started keeping track of every sailor’s service throughout his career, and assigned him a “continuous service” or “official number” that he carried from ship to ship. The Continuous Service Engagement Books from 1853 to 1872, and then the Registers of Seamen’s Services from 1873 onwards, can readily be searched using the references shown below. In these records are found the date and place of birth. Along with Royal Navy service on ships and at stations, these records may also show any service with the Merchant Marine. The physical description is provided, along with naval engagements and battles. The occupation or rating—like “stoker”—will be noted. Consider the following example and case study.

Sydney John Pinsent (born 1893)—stoker & the Battle of Jutland, 1916

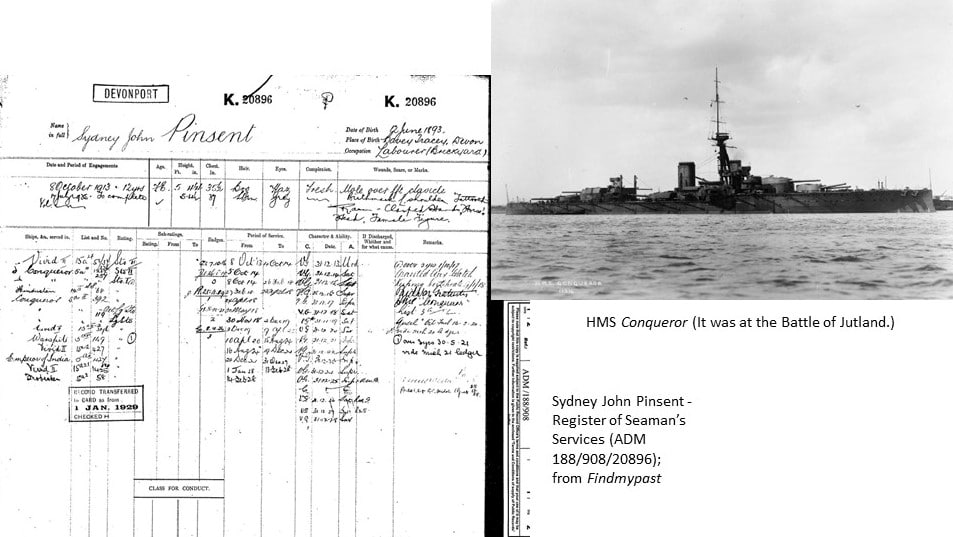

During the pandemic, The National Archives (TNA) continues to offer free downloads from their online images of records for people who register on their site. From the “Register of Services,” a document was obtained related to Sydney John Pinsent, born 1893 in Bovey Tracey, Devon, who I randomly selected.[3] He had been a brickyard worker when he entered the service in 1913 at age 20 at HMS Vivid II, which was not a ship but rather the Stokers and Engine Room Artificers School in Devonport. This occupation suggests that he may have been the son of John and Ann Pinsent, who according to the 1901 census of Bovey Tracey, labored in the “Brick Works.” His Official Number was K.20896. Distinguishing features such as a mole, a birthmark, tattoos, etc. were noted, along with his height of 5’ 4 ½” in 1913. His character ranged from satisfactory to superior as he fulfilled his duties as a stoker and eventually as a leading stoker. In 1916, during the First World War, he served on HMS Conqueror at the important Battle of Jutland; however, the outcome and winner of the battle are still debated by scholars today.[4]

Pinsent was a career seaman who mostly stayed in the navy until 1945, at the end of World War II. In 1929, his service was continued on a separate form, which lists every ship he was on until October 1935 when he was pensioned.[5] He again returned to service in 1938 and carried on until August 1945. He was a leading stoker the whole time and his character was always “v.g.” or very good, and his efficiency was “superior.” This record indicates that he was awarded the D.S.M. (Distinguished Service Medal) in 1942, and that it was reported in the London Gazette. According to another database, he was awarded the Royal Navy Long Service and Good Conduct Medal.[6] Medals of this type are another source for military service.

This is a lot of information on a regular sailor. For greater context and appreciation, one can also research the history of what each ship was doing during the time an ancestor served on it, which brings the man’s story more to life.

-----------------------------------------

Many excellent books have been written on the Royal Navy, including very good ones for genealogists and family historians.

- Simon Fowler, Tracing Your Naval Ancestors: A Guide for Family Historians (Barnsley, Yorkshire: Pen and Sword Books Ltd., 2011).

- Bruno Pappalardo, Tracing Your Naval Ancestors, Readers’ Guide No. 24 (Richmond, Surrey: Public Record Office, 2003).

- A. M. Rodger, Naval Records for Genealogists, Public Record Office Handbook No. 22 (Richmond, Surrey: PRO Publications, 1998).

- Ian Waller, My Ancestor was in The Royal Navy: A Guide to Sources for Family Historians (London: Society of Genealogists Enterprises Ltd., 2014).

There are also numerous good books, online resources, and archival collections for operational histories and concerning the ships themselves.

- “Royal Navy operations and correspondence 1660-1914,” Research Guide, The National Archives (https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/royal-navy-operations-correspondence-1660-1914/)

- “Royal Navy ships’ voyages in log books,” Research Guide, The National Archives (https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/royal-navy-ships-voyages-log-books/)

- “Logs and journals of ships of exploration,” Research Guide, The National Archives (https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/logs-journals-ships-of-exploration-1757-1904/)

- “Royal Navy First World War Lives at Sea,” Royal Museums Greenwich (https://royalnavyrecordsww1.rmg.co.uk)

- “Trafalgar Ancestors” (1805), database, The National Archives (https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/trafalgarancestors/) (mentioned in part 1)

- Rif Winfield, British Warships in the Age of Sail 1817-1863: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates (Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Seaforth Publishing; an imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd., 2014). By the same author, see British Warships in the Age of Sail 1714-1792; British Warships in the Age of Sail 1603-1714; British Warships in the Age of Sail 1793-1817.

The National Archives has published several Research Guides to help trace ancestors who were ratings:

- “Royal Navy ratings up to 1913,” Research Guide, The National Archives (https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/royal-navy-ratings-up-to-1913/)

- “Royal Navy ratings’ service records 1853-1928,” Research Guide, The National Archives (https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/royal-navy-ratings-service-records-1853-1928/)

- “Royal Navy ratings of the First World War,” Research Guide, The National Archives (https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/royal-navy-ratings-of-the-first-world-war/)

- “Royal Navy ratings’ pensions 17th-20th centuries,” Research Guide, The National Archives (https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/royal-navy-ratings-pensions/)

- “Royal Navy ratings: further research,” Research Guide, The National Archives (https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/royal-navy-ratings-further-research/)

Great adventures await you as you explore the lives of your ancestors, and it is particularly enjoyable to learn more about them in the context of the times in which they lived. Our skilled researchers at Price Genealogy are here to help.

by Greg

[1] “Royal Navy ranks, rates, and uniforms of the 18th and 19th centuries,” Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Royal_Navy_ranks,_rates,_and_uniforms_of_the_18th_and_19th_centuries).

[2] Bruno Pappalardo, Tracing Your Naval Ancestors (Richmond, Surrey: Public Record Office, 2003), pp. 90-97.

[3] “UK, Royal Navy Registers of Seamen’s Services, 1848-1939,” Ancestry (www.ancestry.com), entry for Sydney John Pinsent, born 12 June 1893, first service 8 October 1913 on HMS Vivid II shore establishment, service number K.20896.

[4] “British Royal Navy & Royal Marines, Battle of Jutland 1916 Servicemen,” Findmypast (www.findmypast.com), entry for Sydney John Pinsent, HMS Conqueror; citing The National Archives, ADM 188/908/20896. This is the same image as was found in Ancestry’s Register of Seamen’s Services.

[5] “UK, Royal Navy Registers of Seamen’s Services, 1848-1939,” Ancestry (www.ancestry.com), two-page entry for Sydney John Pinsent, born 12 June 1893, first service under new system 11 September 1929 on HMS Frobisher, service number K.20896.

[6] “UK, Naval Medal and Award Rolls, 1793-1972,” Ancestry (www.ancestry.com), entry for Sidney John Pinsent, HMS Frobisher, 17 December 1928.