Scots-Irish Ancestors Book Review

22

22Feb

Book review: Researching Scots-Irish Ancestors: The essential guide to early modern Ulster, 1600-1800, 2nd edition

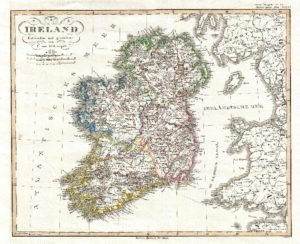

Toward the end of 2018, the Ulster Historical Foundation published William J. Roulston’s second edition of Researching Scots-Irish Ancestors: The essential genealogical guide to early modern Ulster, 1600-1800. In the United Kingdom the book is sold under the title Researching Ulster Ancestors. Ulster is an ancient Irish province that consists of all of Northern Ireland: Antrim, Down, Armagh, Derry, Fermanagh, and Tyrone Counties and three counties now in the Republic of Ireland: Cavan, Monaghan, and Donegal. Those looking for a guide on researching all of Ireland in all periods will find John Grenham’s Tracing Your Irish Ancestors, 4th edition, a welcome addition to their personal library. Roulston’s guide on early modern Ulster, although focused on a specific period and region, spans an impressive 606 pages. This time and place deserves attention. Even the most experienced professionals often find it difficult to do this research, yet there are many in the United States and elsewhere who long to connect with their Irish roots in this period. This is prior to the period when census, civil registration, and church records are widely available. Many of the traditionally valued collections have been destroyed in full or in part as a result of the religious and political fighting over the years in Ireland. Many who have tried Irish research may have heard of the Public Records Office fire at Dublin Four Courts in 1922 that destroyed many of Ireland’s genealogically useful records. This situation makes Roulston’s guide especially valuable as it lists many surviving sources, and describes how they may be used.

The first half of the book has readable chapters covering various issues and sources. These chapters are particularly well organized so that topics can be easily referenced, as needed. Roulston does more here than describe available sources, and give examples. He understands and conveys the value of each type of record; he also outlines common issues and solutions. Common issues discussed include variations in Irish surname spelling and jurisdictional issues such as boundaries. The second half of the book is made up of useful appendices. The largest of these is some 200 pages listing available sources by parish. Other appendices include lists of estate records collections, archives and libraries, and a list of some 600 geographical features or locations and the parish and county in which each are located.

Roulston’s work dispels the idea that research in this period is impossible. At the same time, he does not attempt to fool the reader into thinking it will be easy. Instead, he gives an honest appraisal of the difficulty of using the various sources. Some sources listed can be accessed online, or from the United States on microfilm. However, there are many useful collections located only in Belfast, Ireland, or in locations around the United Kingdom. There are full chapters dedicated to discussing many of the available sources: church records, gravestone inscriptions, landed estate records, the Registry of Deeds, wills and testamentary papers, military records, newspapers and books, emigration, records relating to government and the legal system, and parliamentary election records. There are a few chapters that group similar record types: business and occupation; education, charity, and hospital records; records of organizations, clubs, and societies; and a chapter on diaries, journals, memoirs, and correspondence. There are more general chapters that group miscellaneous seventeenth-century records, and eighteenth-century records. These chapters include, among other records, plantation records, military records, land or court records, census substitutes, and penal law records. From this list it can be seen that Roulston discussed well-known sources and large collections, as well as the more obscure or lesser known collections about which his readers may have been entirely unaware.

Those who are more familiar with early English or Scottish research will recognize that many of the same types of records are useful for Irish research. The researcher may even wish to study the guides on these areas for additional insight. Some recommended books covering these areas and record types, which also apply to Ireland, include the following: Herber’s Ancestral Trails,[1] Clarke’s Tracing Your Scottish Ancestors,[2] Stuart’s Manorial Records,[3] Tate’s The Parish Chest,[4] and Durie’s Understanding Documents.[5] Roulston goes over early Irish history and migrations, providing contextual understanding for what types of sources exist. Roulston explains where collections of each of these record types are available, and summarizes what is known to exist. Even after his thorough listing of sources, Roulston expresses the everlasting hope of every genealogist when he states “some collections remain in private custody, perhaps still waiting rediscovery.”[6] It is clear from the wealth of sources discussed that a lifetime could be spent in researching one person’s Ulster ancestry.

Even for readers already aware of all these collections, Roulston adds value with his perspective. United States genealogists will naturally have different expectations about these records, as some records of the same type are used in United States research. Even the names of the records may set incorrect expectations as the names may be used differently. For example, many cities in Ulster have corporation records. A United States researcher at first exposure to the term may suppose these are business records, as businesses in the United States are often referred to as corporations. In Ireland, the cities themselves were referred to as corporations. Thus, the corporation records are city government administration records, often referred to as city or town records in United States research. Roulston sets realistic expectations for the reader. There is some unique legal and historic context that surrounds the records in Ireland that affects what was recorded or survives. For example, the religious situation with the Church of Ireland had a big impact on record keeping. Those who were members of a different church can often be found among the registers of the Church of Ireland due to the legal situation at the time. In addition to appearing among the baptisms, marriages, and burials, many residents of a parish will appear in the vestry minutes. All the records Roulston discusses are not necessarily genealogical goldmines. Records often list little more than a name. Many types of records have low population coverage. For example, only a small percentage of the population would appear in a deed due to land ownership practices, as well as due to the registration of deeds being optional. Many record types even purposely exclude certain populations (such as Catholics being excluded in some records). Even alongside this honest appraisal of the records, Roulston restores hope. For instance, he mentions how Catholics may sometimes appear even in records where they were supposed to be excluded, and that sometimes more information is given in records than expected. His examples of what records might contain motivate the potential researcher to continue looking. Roulston shares examples of estate records giving emigration dates;[7] registered deeds including marriages or wills;[8] wills that show emigration of a witness;[9] a gravestone that states it was erected by a son of the deceased after a long absence from Ireland;[10] election records that give relationships, approximate death dates of relatives, or country to which emigrated;[11] and baptism records that were thought not to exist, which may appear among the church’s vestry minutes.[12] One example of the importance of understanding the legal and historical context is the influence of land ownership laws on record keeping. Often the reason for listing emigration or death date data in records related to land or elections (only land owners or lessees could vote), is that many leases were for lives (i.e. leases that were good until a certain list of people each died). Therefore, listing when a certain person died was relevant to whether the surviving resident still maintained a valid lease.

Roulston’s guide is thorough, well-reasoned, and insightful. His genealogical experience shows up throughout the guide, making it in part a hidden gem on general genealogical methodology as well as a guide on early Ulster research. A researcher can use the various sections on different records, and the list of sources by parish, to compile a research plan for any early Ulster research problem. Anyone researching early modern Ulster should pick up a copy.

Price Genealogy has researchers qualified to research your Irish ancestry. Please inquire with us today.

Michael

[1] Mark Herber, Ancestral Trails: The Complete Guide to British Genealogy and Family History, 2nd ed. (Baltimore, Maryland: Genealogical Publishing Company, Inc, 2006).

[2] Tristram Clarke, Tracing Your Scottish Ancestors: The Official Guide, 6th ed. (Edinburgh, Scotland: National Records of Scotland, 2011).

[3] Denis Stuart, Manorial Records (Andover, Hampshire, England: Phillimore & Co. Ltd, 2010).

[4] W. E. Tate, The Parish Chest, 3rd ed. (Stroud, Gloucestershire: Phillimore & Co. Ltd, 2011).

[5] Bruce Durie, Understanding Documents for Genealogy & Local History (Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press, 2013).

[6] William J. Roulston, Researching Scots-Irish Ancestors: The essential genealogical guide to early modern Ulster, 1600-1800, 2nd ed. (Belfast: Ulster Historical Foundation, 2018), 135.

[7] Ibid, 141.

[8] Ibid, 153-154.

[9] Ibid, 154.

[10] Ibid, 78.

[11] Ibid, 180.

[12] Ibid, 40.