The Workhouse Part 1

25

25Jan

Even today, almost 90 years after the last workhouse was closed in England, most of us still know that the workhouse was a place to be dreaded and was a last resort in times of abject poverty. But, is that the whole truth about the workhouse? Was it only the desperately poor who ended up in the workhouse? Could yours have spent time in the workhouse? Here's how you can search workhouse records to find out!

Workhouse Records

A very brief history of workhouses and the Poor Law:

- 1601 – Parishes were responsible for assisting their own poor.

- 1723 – An Act of Parliament formalized the establishment of workhouses to assist the poor who could not work.

- 1834 – A new Poor Law was created to establish a national system of poor relief. The workhouse was now the only option for the poor who had no family support.

- 1948 - National Health Service was inaugurated, putting an end to workhouses.

Why was the workhouse so dreaded?

- It was a very public humiliation – everyone in the parish would know the individual or family had gone to the workhouse. It was no longer possible to receive financial help from the church and remain in your own home.

- Families would be separated – husbands and wives in different buildings, children over 3 separated from their mothers. Siblings were also separated.

- Workhouse residents often had the feeling that they would never get out, which the elderly especially dreaded.

- Residents feared that their body would be buried in a pauper’s grave, or even used for anatomical dissection.

- Work and working conditions were miserable.

- Food was poor and monotonous.

- Medical care for the ill or elderly was very poor.

- Residents, including children, lived alongside the “insane.”

- Cruelty and disease were often reported.

The government’s goal was to make the workhouse less desirable than the lowest condition of poverty outside the workhouse. This was intended to make the indigent want to provide for themselves rather than face the workhouse. Some people said, “I’d rather die than go into the workhouse,” and some did die rather than go to the workhouse. On 8 August 1894, London’s East End police were called to a house in the area called Bow. An unemployed packer, Charles Hatton, and his wife Eliza, had committed suicide. They left a note which said, “We have been forced to this rash act as we can stand it no longer and we dread going to the workhouse.”

Why did people go to the workhouse?

- Finances – this was the obvious reason, but once you were in the workhouse you could not earn money to get out!

- Widowhood – there was very little “honest” work for widows. Both elderly and young widows with children often found themselves in the workhouse.

- Illegitimacy – unless the family of the mother of an illegitimate child could support them, the workhouse might be their only option. This became a greater problem during Industrial Revolution. It was easier to support “one extra mouth” on a farm than in an industrialized town where housing was crowded and all food had to be purchased.

- Insanity – there was no other option for the poor who had mental health issues. No distinction between postpartum depression and violent mental health issues was recognized, and many women with postpartum issues were sent to the workhouse as insane and some ended up staying there.

- Old age – there was no Social Security or pension! Often adult children did not have space or money to support their parents.

- Illness – chronic illness, loss of limbs, etc., meant an inability to work and no option other than the workhouse.

A practical example of using workhouse records

I have long known that my third great grandparents, John Minting and his wife Margaret, had a son named Albert Alonzo, my second great grandfather, who had been baptized in 1817 at St. Marylebone, London. I had found a potential death index record in 1847 for John Minting, aged 80, in the St. Martin-in-the-Fields Registration District. At that time, this is all that I knew.

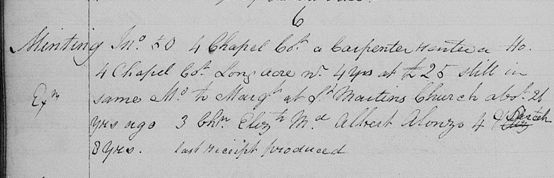

Much later, I learned about a new record collection at www.findmypast.com called the “London Poor Law Records, 1581-1899.” Searching for the Minting surname, I found the following document:

The document is tricky to read but it tells me that in 1822 John Minting, age 50, who was living at 4 Chapel Court, Long Acre, had received 25 pounds per year for four years from the parish. It tells me that he had been married to a woman named Margaret for 26 years and that he had married her at St. Martin-in-the-Fields. It also tells me that he has three children—Elizabeth, Albert Alonzo, age 4, and Sarah, age 3. This record told me that Albert had at least two living siblings in 1822.

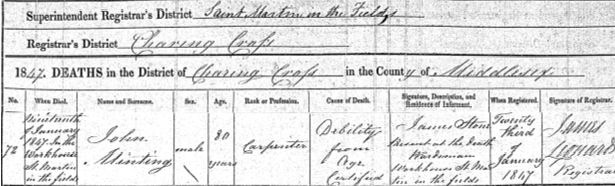

I learned that John and Margaret Minting in 1822 had been married for about 26 years, giving an approximate marriage year of 1796 and the marriage location of St. Martin’s church. It took very little time to find the marriage record dated 18 October 1796 for John Minting and Margaret Barnerd in St. Martin-in-the-Fields. This family was not doing well financially, so I searched for the Minting name in records of the poor in London. Thanks to the “London, England, Workhouse Admission and Discharge Records, 1764-1930” on www.ancestry.com, John Minting’s exact death date on 19 January 1847 was found. It was recorded in the Westminster “Castle Street Workhouse Register, 1837-1848,” giving his age as 75, and underneath his name he was sadly listed as insane. At age 75, he may have been suffering from dementia. The death certificate for John Minting was ordered and it confirmed his death in the workhouse and it showed his occupation as carpenter. His cause of death was listed a little kindlier as “debility from age,” and he was age 80 here.

John Minting’s death in 1847 suggested that he would only be found in one census record. He was recorded in the 1841 census with a different wife, indicating that his first wife, Margaret, had died before 1841.

This example of workhouse research for the Minting family shows how workhouse records can aid in building the framework facts of a family history while also giving rich details to your family’s story.

There were more than 6,000 workhouses in England and Wales. Searching them can be a long process, and not all workhouse records survive.

What types of workhouse records can you expect to find to help with your family that spent time in the workhouse?

- admission and discharge records.

- apprenticeship papers

- hospital admissions

- school records

- creed registers

- baptism registers

In the next workhouse blog we will examine the information you may find about your ancestors through workhouse records and how to access the records.

At Price Genealogy we have over forty years of experience helping people with the unique challenges of their family history, including research beyond baptisms, marriages and burials.

Lindsey

Have you found any information on your ancestors through workhouse records? Let us know in a comment below!